Abstract

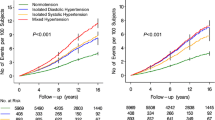

Risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) increases incrementally with blood pressure, even within the high-normal range. In the general population, 27% of CVD in women and 37% in men is attributable to hypertension. A high percentage of these hypertension-related events occur in those with high-normal blood pressure and mild hypertension; about one-fourth of CVD events in elderly women and one-third in elderly men in the Framingham Study occured in persons who had blood pressures of 140–159mm Hg systolic and/or 90–95mm Hg diastolic. The average systolic blood pressure (SBP) at which coronary heart disease occurs is rather modest (141mm Hg), as is the pulse pressure (59–63mm Hg). Of the CVD events in elderly participants in the Framingham Study, 24% in men and 36% in women occurred in persons receiving treatment for hypertension.

There is a growing recognition of the importance of the systolic component of blood pressure. About 65% of hypertension in the elderly is isolated systolic hypertension (ISH), and CVD risk increases with pulse pressure. Pulse pressure is not simply a marker for stiff diseased arteries; treatment of ISH in trials promptly reduces the CVD risk, indicating that the pulse pressure generated by the stiff artery is the culprit. Analysis of data from clinical trials indicates that greater reliance should be placed on systolic pressure in evaluating the CVD potential of hypertension.

Hypertension, including ISH, seldom occurs in isolation from other risk factors and overt CVD. Risk varies widely depending on the burden of accompanying risk factors. This makes global risk assessment mandatory for evaluating risk and the urgency and nature of treatment required.

Evidence incriminating systolic pressure as the dominant blood pressure determinant of CVD has not been translated into clinical practice. Most of the uncontrolled hypertension observed in the Framingham Study is concentrated in those with ISH. This also extends to African-Americans, people with diabetes mellitus and the elderly.

When should SBP be considered controlled? Substantial evidence supports the value of treating ISH with SBP exceeding 160mm Hg. Trial data are not yet available to support recommendations to treat lesser elevations of ISH or pulse pressure per se, but since one-half of patients with mild ISH have two or more additional risk factors, most are candidates for treatment. In such patients, ISH should be considered controlled when their global CVD risk is reduced to below the average for their age.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Arch Intern Med 1997; 157: 2413–244

Kannel WB. Risk stratification in hypertension: new insights from the Framingham Study. Am J Hypertens 2000; 13: 3–10s

Anon. Morbidity and mortality: 2000 chartbook on cardiovascular, lung and blood diseases. National Institutes of Health, NHLBI

SHEP Cooperative Research Group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension: final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). JAMA 1991; 265: 3255–64

Kannel WB. Prospects for prevention of cardiovascular disease in the elderly. Prev Cardiol 1998; 1: 32–9

Vasan RS, Larson MG, Leip EC, et al. Assessment of frequency of progression to hypertension in non-hypertensive participants in the Framingham Study: a cohort study. Lancet 2001; 358: 1682–6

Kannel WB. Blood pressure as a cardiovascular risk factor: prevention and treatment. JAMA 1996; 275: 1571–6

Kannel WB, Garrison RJ, Dannenberg AL. Secular trends in blood pressure in normotensive persons: The Framingham Study. Am Heart J 1993; 125: 1154–8

Vasan RS, Beiser A, Seshadri S, et al. Residual lifetime risk of developing hypertension in middle-aged women and men: The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA 2002; 287: 1003–10

Kannel WB, Dannenberg AL, Abbott RD. Unrecognized myocardial infarction and hypertension: The Framingham Study. JAMA 1985; 109: 81–5

Franklin SS, Khan SA, Wong ND, et al. Is pulse pressure useful in predicting risk for coronary heart disease? The Framing-ham Heart Study. Circulation 1999; 100(4): 354–60

Rutan G, McDonald RH, Kuller LH. A historical perspective of elevated systolic versus blood pressure from an epidemiological and clinical viewpoint. J Clin Epidemiol 1998; 42: 663–73

Kannel WB, Schwartz MJ, McNamara PM. Blood pressure and risk of coronary heart disease. The Framingham Study. Dis Chest 1969; 56: 43–52

Neaton JD, Kuller L, Stamler J, et al. Impact of systolic and diastolic blood pressure on cardiovascular mortality. In: Laragh JH, Brenner BM, editors. Hypertension: pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. New York (NY): Raven Press, 1995: 127–144

Wilking SVP, Belanger A, Kannel WB, et al. Determinants of isolated systolic hypertension. JAMA 1998; 260: 3451–5

Kannel WB. Elevated systolic blood pressure as a cardiovascular risk factor. Am J Cardiol 2000; 85(2): 251–5

Dart AM, Kingwell BA. Pulse pressure: a review of mechanism and clinical relevance. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001; 37: 975–84

Staessen JA, Fagard R, Thijs L, et al. Randomized doubleblind comparison of placebo and active treatment for older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Lancet 1997; 350: 757–64

Kannel, Dawber TR, McGee DL. Perspectives on systolic hypertension: The Framingham Study. Circulation 1980; 61: 1179–82

Reaven GM. Banting Lecture: role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes 1988; 37: 1595–607

Wilson PWF, D’Agostino RB, Levy D, et al. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation 1998; 97: 1837–47

European Society of Hypertension. Update on hypertension management. J Hypertens 2002; 20: 153–5

Franklin SS. Is there a preferred antihypertensive treatment for isolated systolic hypertension and reduced arterial compliance? Curr Hypertens Rep 2000; 2: 253–9

Ferrier KE, Muhlmann MH, Baquet JP, et al. Intensive cholesterol reduction lowers blood pressure and large artery stiffness in isolated systolic hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39: 1020–5

Lloyd-Jones DM, Evans JC, Larson MG, et al. Differential control of systolic and diastolic blood pressure: factors associated with lack of blood pressure control in the community. Hypertension 2000; 36: 504–9

Burt VL, Whelton P, Roccella EJ, et al. Prevalence of hypertension in the US adult population; results from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1991. Hypertension 1995; 25: 305–13

Coca A. Actual blood pressure control: are we doing things right? J Hypertens 1998; 16Suppl. 1: S45–51

Hosi J, Wiklund I. Managing hypertension in general practice. J Hum Hypertens 1995; 9Suppl. 2: S19–23

Coppola WG, Whincup PH, Walker M, et al. Identification and management of stroke risk in older people: a national survey of current practice in primary care. J Hum Hypertens 1997; 11: 185–91

Berlowitz DR, Ash AS, Hickey EC, et al. Inadequate management of high blood pressure in a hypertensive population. N Engl J Med 1998; 339: 1957–63

Forette F, Seux MI, Staessen JA, et al. Prevention of dementia in randomized double-blind placebo-controlled Systolic Hypertension in Europe Trial (Syst-Eur). Lancet 1998; 352: 1347–51

Sacks FM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM, et al. Effect on blood pressure of reduced sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 3–10

Bloom BS. Continuation of initial antihypertensive medication after 1 year of therapy. Clin Ther 1998; 20: 671–81

Hill MN, Bone LR, Kim MT, et al. Barriers to hypertension care and control in young urban black men. Am J Hypertens 1999; 12: 951–8

Acknowledgements

Framingham Study research is supported by NIH/NHLBI contract N01-HC-25195, and the Visiting Scientist Program is supported by Servier Amerique. The author has been a consultant for Astra-Zeneca and a speaker for programs sponsored by Bristol Myers Squibb and Pfizer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kannel, W.B. Prevalence and Implications of Uncontrolled Systolic Hypertension. Drugs Aging 20, 277–286 (2003). https://doi.org/10.2165/00002512-200320040-00004

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00002512-200320040-00004