Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To measure how often a breast-related concern was documented in medical records after screening mammography according to the mammogram result (normal, or truenegative vs false-positive) and to measure changes in health care utilization in the year after the mammogram.

DESIGN: Cohort study.

SETTING: Large health maintenance organization in New England.

PATIENTS: Group of 496 women with false-positive screening mammograms and a comparison group of 496 women with normal screening mammograms, matched for location and year of mammogram.

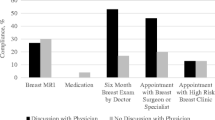

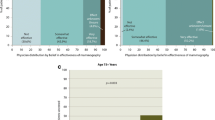

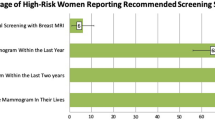

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS: 1) Documentation in clinicians’ notes of patient concern about the breast and 2) ambulatory health care utilization, both breast-related and non-breast-related, in the year after the mammogram. Fifty (10%) of 496 women with false-positive mammograms had documentation of breast-related concern during the 12 months after the mammogram, compared to 1 (0.2%) woman with a normal mammogram (P=.001). Documented concern increased with the intensity of recommended follow-up (P=.009). Subsequent ambulatory visits, not related to the screening mammogram, increased in the year after the mammogram among women with false-positive mammograms, both in terms of breast-related visits (incidence ratio, 3.07; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.69 to 5.93) and non-breast-related visits (incidence ratio, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.25).

CONCLUSIONS: Clinicians document concern about breast cancer in 10% of women who have false-positive mammograms, and subsequent use of health care services are increased among women with false-positive mammogram results.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Brown ML, Houn F, Sickles EA, Kessler LG. Screening mammography in community practice: positive predictive value of abnormal findings and yield of follow-up procedures. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165:1373–7.

Elmore JG, Barton MB, Moceri VM, Polk S, Arena PJ, Fletcher SW. Ten-year risk of false-positive screening mammograms and clinical breast examinations. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1089–96.

Lerman C, Trock B, Rimer BK, Boyce A, Jepson C, Engstrom PF. Psychological and behavioral implications of abnormal mammograms. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:657–61.

Gram IT, Lund E, Slenker SE. Quality of life following a false positive mammogram. Br J Cancer. 1990;62:1018–22.

Ellman R, Angeli N, Christians A, Moss S, Chamberlain J, Maguire P. Psychiatric morbidity associated with screening for breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1989;60:781–4.

Swanson V, McIntosh IB, Power KG, Bobson H. The psychological effects of breast screening in terms of patients’ perceived health anxieties. Br J Clin Pract. 1996;50:129–35.

Johnston ME, Gibson ES, Terry CW, et al. Effects of labelling on income, work and social function among hypertensive employees. J Chronic Dis. 1984;37:417–23.

Haynes RB, Sackett DL, Taylor DW, Gibson ES, Johnson AL. Increased absenteeism from work after detection and labeling of hypertensive patients. N Engl J Med. 1978;299:741–4.

Reid MC, Schoen RT, Evan J, Rosenberg JC, Horwitz RI. The consequences of overdiagnosis and overtreatment of Lyme disease: an observational study. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:354–62.

Healy BP, Breast cancer in the news: the rise of consumer power in medical care [editorial]. J Womens Health. 1997;6:141–2.

Welch HG, Fisher ES. Diagnostic testing following screening mammography in the elderly. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1389–92.

Linver M, Osuch J, Brenner R, Smith R. The mammography audit: a primer for the Mammography Quality Standards Act (MQSA). AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165:19–25.

Sickles EA. Quality assurance: how to audit your own mammography practice. Radiol Clin North Am. 1992;30:265–75.

Bassett L, Hendrick R, Bassford T, et al. Quality determinants of mammography. Clinical practice guideline no. 13. Rockville, Md: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1994.

Kerlikowske K, Grady D, Barclay J, Sickles EA, Ernster V. Likelihood ratios for modern screening mammography: risk of breast cancer based on age and mammographic interpretation. JAMA. 1996;276:39–43.

Bird R. Low-cost screening mammography: report on finances and review of 21, 716 consecutive cases. Radiology. 1989;171:87–90.

Robertson C. A private breast imaging practice: medical audit of 25,788 screenings and 1,077 diagnostic examinations. Radiology. 1993;187:75–9.

Lindsey JK, Jones B. Choosing among generalized linear models applied to medical data. Stat Med. 1998;17:59–68.

Christiansen CL Morris CN. Hierachical poisson regression modeling. J Am Stat Assoc. 1997;92:618–32.

Stokes ME, Davis CS, Koch GG. Categorical Data Analysis Using the SAS System. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 1997:465.

Fentiman IS. Pensive women, painful vigils: consequences of delay in assessment of mammographic abnormalities. Lancet. 1988;1041–2.

Ong G, Austoker J, Brett J. Breast screening: adverse psychological consequences one month after placing women on early recall because of diagnostic uncertainty. A multicentre study. J Med Screening. 1997;4:158–68.

Scaf-Klomp W, Sanderman R, van de Wiel HB, Otter R, van den Heuvel WJ. Distressed or relieved? Psychological side effects of breast cancer screening in The Netherlands. J Epidemiol Comm Health. 1997;51:705–10.

Sutton S, Saidi G, Bickler G, Hunter J. Does routine screening for breast cancer raise anxiety? Results from a three wave prospective study in England. J Epidemiol Comm Health. 1995;49:413–8.

Olsson P, Armelius K, Nordahl G, Lenner P, Westman G. Women with false positive screening mammograms:how do they cope? J Med Screening. 1999;6:89–93.

Lindfors KK, O’Connor J, Acredolo CR, Liston SE. Short-interval follow-up mammography versus immediate core biopsy of benign breast lesions: assessment of patient stress. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:55–8.

Gilbert FJ, Cordiner CM, Affleck IR, et al. How anxiogenic is recall following breast screening and does a family history of breast cancer make a difference? Psycho-Oncology. 1995;4:88. Abstract.

Brett J, Austoker J, Ong G. Do women who undergo further investigation for breast screening suffer adverse psychological consequences? A multi-centre follow-up study comparing different breast screening result groups five months after their last screening appointment. J Public Health Med. 1998;20:396–403.

Weil JG, Hawker JI. Positive findings of mammography may lead to suicide (letter). Br Med J. 1997;314:754–4.

Cadman D, Chambers LW, Walter SD, Ferguson R, Johnston N, McNamee J. Evaluation of public health preschool child developmental screening: the process and outcomes of a community program. Am J Public Health. 1977;77:45–51.

Paskett ED, Rimer BK. Psychosocial effects of abnormal pap tests and mammograms: a review. J Womens Health. 1995;4:73–82.

Peshkin BN, Lerman C. Genetic counselling for hereditary breast cancer. Lancet. 1999;353:2176–7.

Brenner R, Pfaff JM. Mammographic changes after excisional breast biopsy for benign disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167:1047–52.

Rimer BK. Putting the “informed” in informed consent about mammography. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:703–4.

Sickles EA. False positive rate of screening mammography [letter]. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:561–2.

Liu S, Bassett LW, Sayre J. Women’s attitudes about receiving mammographic results directly from radiologists. Raiology. 1994;193:783–6.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This study was supported by the Thomas O. Pyle fellowship and a project grant from the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Foundation and by the American Cancer Society. Dr. Elmore was the recipient of a Robert Wood Johnson Generalist Faculty Arward.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Barton, M.B., Moore, S., Polk, S. et al. Increased patient concern after false-positive mammograms. J GEN INTERN MED 16, 150–156 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00329.x

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00329.x