Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To assess the effect of physician training on management of depression.

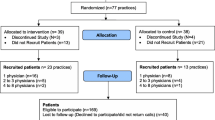

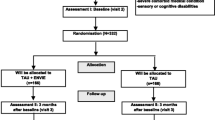

DESIGN: Primary care physicians were randomly assigned to a depression management intervention that included an educational program. A before-and-after design evaluated physician practices for patients not enrolled in the intervention trial.

SETTING: One hundred nine primary care physicians in 2 health maintenance organizations located in the Midwest and Northwest regions of the United States.

PATIENTS/PARTICIPANTS: Computerized pharmacy and visit data from a group of 124,893 patients who received visits or prescriptions from intervention and usual care physicians.

INTERVENTIONS: Primary care physicians received education on diagnosis and optimal management of depression over a 3-month training period. Methods of education included small group interactive discussions, expert demonstrations, role-play, and academic detailing of pharmacotherapy, criteria for urgent psychiatric referrals, and case reviews with psychiatric consultants.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS: Pharmacy and visit data provided indicators of physician management of depression: rate of newly diagnosed depression, new prescription of antidepressant medication, and duration of pharmacotherapy. One year after the training period, intervention and usual care physicians did not differ significantly in the rate of new depression diagnosis (P=.95) or new prescription of antidepressant medicines (P=.10). Meanwhile, patients of intervention physicians did not differ from patients of usual care physicians in adequacy of pharmacotherapy (P=.53) as measured by 12 weeks of continuous antidepressant treatment.

CONCLUSIONS: After education on optimal management of depression, intervention physicians did not differ from their usual care colleagues in depression diagnosis or pharmacotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Executive Summary. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; March 2001:2.

Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health; 1999.

Public Health Service Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Depression in Primary Care. Vol. 2. Treatment of Major Depression. Rockville, Md: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1993. AHCPR publication no. 93-0551.

Schulberg HC, Block MR, Madonia MJ, et al. The usual care of major depression in primary care practice. Arch Fam Med. 1997;6:334–9.

Wang PS, Berglund P, Kessler RC. Recent care of common mental disorders in the United States, prevalence and conformance with evidence-based recommendations. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:284–92.

Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19.

Davis D, O’Brien MA, Freemantle N, Wolf FM, Mazmanian P, Taylor-Vaisey A. Impact of formal continuing medical education: do conferences, workshops, rounds and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? JAMA. 1999;282:867–74.

Thompson C, Kinmonth AL, Stevens L, et al. Effects of a clinicalpractice guideline and practice-based education on detection and outcome of depression in primary care: Hampshire Depression Project Randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;355:185–91.

Soumerai SB. Principles and uses of academic detailing to improve the management of psychiatric disorders. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1998;28:81–96.

Thomson O’Brien MA, Oxman AD, Davis DA, Haynes RB, Freemantle N, Harvey EL. Audit and feedback versus alternative strategies: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;2:CD000260.

Roter DL, Hall JA, Kern DE, Barker LR, Cole KA, Roca RP. Improving physicians’ interviewing skills and reducing patients’ emotional distress. A randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 1995;55:1877–84.

Gerrity MS, Cole SA, Dietrich AJ, Barrett JE. Improving the recognition and management of depression: is there a role for physician education? J Fam Pract. 1999;48:949–57.

Gask L. Small group interactive techniques utilizing videofeedback. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1998;28:97–1136.

Tiemens BG, Ormel J, Jenner JA, et al. Training primary-care physicians to recognize, diagnose and manage depression: does it improve patient outcomes? Psychol Med. 1999;29:833–45.

Oxman TE. Effective educational techniques for primary care providers: application to the management of psychiatric disorders. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1998;8:3–9.

Kroenke K, Taylor-Vaisey A, Dietrich AJ, Oxman TE. Interventions to improve provider diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders in primary care. A critical review of the literature. Psychosomatics. 2000;41:39–5.

Katzelnick DJ, Simon GE, Pearson SD, et al. Randomized trial of a depression management program in high utilizers of medical care. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:345–51.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th Ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). HEDIS 2000 Narrative Vol. 1. Item # 10234-100-00. Washington, DC: National Committee for Quality Assurance; 2000.

Armitage P, Berry G. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 3rd Ed. Oxford, England: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1994;428–9.

Simon GE, Von Korff M. Recognition, management and outcomes of depression in primary care. Arch Fam Med. 1995;4:99–105.

McGruder-Habib K, Zung WW, Feussner JR. Improving physicians’ recognition and treatment of depression in general medical care. Results from a randomized clinical trial. Med Care. 1990;28:239–50.

Rubenstein LV, McCoy JM, Cope DW, et al. Improving patient quality of life with feedback to physicians about functional status. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;11:607–14.

Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin EHB, et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care. JAMA. 1995;273:1026–31.

Mynor-Wallis LM, Gath DH, Lloyd-Thomas AR, Tomlinson AR. Randomised controlled trial comparing problem solving treatment with amitriptyline and placebo for major depression in primary care. BMJ. 1995;310:441–5.

Schulberg HC, Block MR, Madonia MJ, et al. Treating major depression in primary care practice. Eight-month clinical outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:913–9.

Simon GE, Von Korff M, Rutter C, Wagner E. A randomized trial of monitoring, feedback, and telephone care management to improve depression treatment in primary care. BMJ. 2000;320:550–4.

Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283:212–20.

Hunkeler EM, Meresman J, Hargreaves WA, et al. Efficacy of nurse telehealth care and peer support in augmenting treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Fam Med. 2000;8:700–8.

Lin EHB, Katon W, Simon G, et al. Achieving guidelines for the treatment of depression in primary care: is physician education enough? Med Care. 1997;35:831–42.

Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Mem Q. 1996;74:511–44.

Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer J, Curry SJ, Wagner EH. Collaborative management of chronic illness. Ann Intern Med. 1997;27:1097–102.

Rollman BL, Hanusa BH, Gilbert T, Lowe HJ, Kapoor WN, Schulberg HC. The electronic medical record. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:189–97.

McCulloch DK, Price MJ, Hindmarsh M, Wagner EH. A population-based approach to diabetes management in a primary care setting: early results and lessons learned. Eff Clin Pract. 1998;1:12–22.

Wagner EH. The role of patient care teams in chronic disease management. BMJ. 2000;430:569–72.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This study was made possible by a grant from Pfizer Pharmaceuticals Inc, New York, NY. We would like to thank Mr. Henry J. Henk and Ms. Kate Bond for their tireless efforts in data programming. Dr. Leslie Taylor contributed to the training of PCPs. We also are indebted to our primary care colleagues at Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound and the Dean Foundation, whose support and enthusiasm were invaluable.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, E.H.B., Simon, G.E., Katzelnick, D.J. et al. Does physician education on depression management improve treatment in primary care?. J GEN INTERN MED 16, 614–619 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009614.x

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009614.x