Abstract

OBJECTIVES: To determine adherence to national guidelines for the secondary prevention of coronary artery disease (CAD) using lipid-lowering drugs (LLDs), by studying the rate of use of LLDs, predictors of use, and the rate of achieving lipid goals, among eligible patients recently hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction.

DESIGN: Cross-sectional analysis of 2,938 medical records, collected from July 1995 to May 1996.

SETTING: Thirty-seven community-based hospitals in Minnesota.

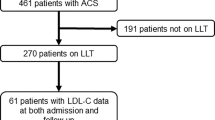

PATIENTS: The 622 patients had previously established CAD and hyperlipidemia (total cholesterol >200 mg/dL or currently using LLDs), and were eligible for LLDs according to the National Cholesterol Education Program II (NCEP II) Guidelines.

MEASUREMENTS: The use of LLDs in eligible patients (primary outcome) and successful achievement of NCEP II goals (total cholesterol <160 mg/dL) among treated patients (secondary outcome).

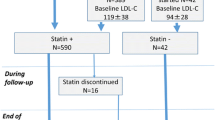

MAIN RESULTS: Only 230 (37%) of 622 eligible patients received LLDs. In multivariate logistic regression, factors independently related to LLD use included age greater than 74 years (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 0.55; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.35, 0.88) and severe comorbidity (AOR 0.60; 95% CI 0.38, 0.95), managed care enrollee (AOR 1.56; 95% CI 1.02, 2.39), past smoker (AOR 1.72; 95% CI 0.98, 3.01), prior revascularization (AOR 2.31; 95% CI 1.51, 3.53), and the use of aspirin (AOR 1.59; 95% CI 1.07, 2.38) or ≥4 medications (AOR 2.89; 95% CI 2.19, 3.84). Of the treated patients who had lipid levels measured (n=149), 15% achieved the recommended goal of a total cholesterol below 160 mg/dL. Of the untreated patients (n=392), 89% were discharged from hospital without a LLD prescription.

CONCLUSIONS: Lipid-lowering drugs, although proven effective for the secondary prevention of CAD, were used by only one third of eligible patients. Among patients receiving LLDs, few achieved recommended lipid goals. Directed quality improvement interventions, such as starting LLDs during hospitalization, may have the potential to substantially reduce CAD morbidity and mortality in this vulnerable population.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Soumerai SB. Factors influencing prescribing. Aust J Hosp Pharm. 1988;18(3):9–16.

Lamas GA, Pfeffer MA, Hamm P, et al. Do the results of randomized trials of cardiovascular drugs influence medical practice? N Engl J Med. 1992;327:241–7.

La Rosa JC, Hunninghake D, Bush D, et al. The cholesterol facts—a summary of the evidence relating dietary fats, serum cholesterol, and coronary heart disease. Circulation. 1990;81:1721–33.

Gaziano JM, Hebert PR, Hennekens CH. Cholesterol reduction: weighing the benefits and risks. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:914–8.

Kjekshus J, Pedersen TR, Tobert JA. Lipid lowering therapy for patients with or at risk of coronary artery disease. Curr Opin Cardiol. 1996;11:418–27.

Gotto AM Jr. Cholesterol management in theory and practice. Circulation. 1997;96:4424–30.

Davignon J, Montigny M, Dufour R. HMG CoA reductase inhibitors: a look back and a look ahead. Can J Cardiol. 1992;8:843–88.

The Expert Panel. Summary of the second report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel II). JAMA. 1993;269:3015–23.

Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group. Randomized trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet. 1994;344:1383–9.

Tsuyuki RT, Teo KK, Ikuta RM, Bay KS, Greenwood PV, Montague TJ. Mortality risk and patterns of practice in 2,070 patients with acute myocardial infarction, 1987–92. Chest. 1994;105:1687–92.

McLaughlin TJ, Soumerai SB, Willison DJ, et al. Adherence to national guidelines for drug treatment of suspected acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:799–805.

Ayanian JZ, Epstein AM. Differences in the use of procedures between women and men hospitalized for coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:221–5.

McLaughlin TJ, Soumerai SB, Willison DJ, et al. The effect of comorbidity on use of thrombolysis or aspirin in acute myocardial infarction patients eligible for treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:1–6.

Soumerai SB, McLaughlin TJ, Gurwitz JH, et al. Effect of local medical opinion leaders on quality of care for acute myocardial infarction: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;279:1358–63.

Gore JM, Goldberg RJ, Matsumoto AS, Castelli WP, McNamara PM, Dalen JE. Validity of serum total cholesterol level obtained within 24 hours of acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1984;54:722–5.

Ryder REJ, Hayes TM, Mulligan IP, Kingswood JC, Williams S, Owens DR. How soon after myocardial infarction should plasma lipid values be assessed? BMJ. 1984;289:1651–3.

Ahnve S, Angelin B, Edhag O, Berglund L. Early determination of serum lipids and apolipoproteins in acute myocardial infarction: possibility for immediate intervention. J Intern Med. 1989;226:297–301.

Greenfield S, Apolone G, McNeil BJ, Cleary PD. The importance of coexistent disease in the occurrence of postoperative complications and one-year recovery in patients undergoing total hip replacement: comorbidity and outcomes after hip replacement. Med Care. 1993;31:141–54.

SAS Institute. SAS/STAT User’s Guide. Version 6. 4th ed. Vol. 2. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 1989.

Efron B, Gong G. A leisurely look at the bootstrap, the jackknife, and cross-validation. Am Statistician. 1983;37:36–48.

Brown BG, Zhao X, Bardsley J, Albers JJ. Secondary prevention of heart disease amongst patients with lipid abnormalities: practice and trends in the United States. J Intern Med. 1997;241:283–94.

Rembold CM. Number-needed-to-treat analysis of the prevention of myocardial infarction and death by antidyslipidemic therapy. J Fam Pract. 1996;42:577–86.

Vogel RA. Risk factor intervention and coronary artery disease: clinical strategies. Coron Artery Dis. 1995;6:466–71.

ASPIRE Steering Group. A British Cardiac Society survey of the potential for the secondary prevention of coronary disease: ASPIRE (Action on Secondary Prevention through Intervention to Reduce Events), principal results. Heart. 1996;75:334–42.

Pearson TA, Peters TD, Feury D. Comprehensive risk reduction in coronary patients: attainment of goals of the AHA guidelines in U.S. patients. Circulation. 1997;96 (suppl):1–733.

McBride P, Schrott HG, Plane MB, Underbakke G, Brown RL. Primary care practice adherence to National Cholesterol Education Program Guidelines for patients with coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1238–44.

Soumerai SB, McLaughlin TJ, Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E, Thibeault G, Goldman L. Adverse outcomes of underuse of beta-blockers in elderly survivors of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1997;277:115–21.

Stafford RS, Blumenthal D, Pasternak RC. Variations in cholesterol management practices of U.S. physicians. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:139–46.

Debusk RF, Houston-Miller N, Superko R, et al. A case-management system for coronary risk factor modification after acute myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:721–9.

Schrott HG, Bittner V, Vittinghoff E, et al. Adherence to National Cholesterol Education Program treatment goals in postmenopausal women with heart disease. JAMA. 1997;277:1281–6.

Marcelino JJ, Feingold KR. Inadequate treatment with HMG CoA reductase inhibitors by health care providers. Am J Med. 1996;100:605–10.

Krumholz HM, Seeman TE, Merril SS, et al. Lack of association between cholesterol and coronary heart disease mortality and morbidity and all-cause mortality in persons older than 70 years. JAMA. 1994;272:1335–40.

Hulley SB, Newman TB. Cholesterol in the elderly: is it important? JAMA. 1994;272:1372–4.

Corti MC, Guralnik JM, Salive ME, et al. Clarifying the direct relation between total cholesterol and death from coronary heart disease in older persons. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:753–60.

Marciniak TA, Ellerbeck EF, Radford MJ, et al. Improving the quality of care for Medicare patients with acute myocardial infarction: results from the Cooperative Cardiovascular Project. JAMA. 1998;279:1351–7.

Ouchi Y, Ohashi Y, Ito H, et al. Serum cholesterol lowering by pravastatin reduces cardiovascular events in the elderly with hypercholesterolemia: overall and age-related analyses of the results from the PATE study. Circulation. 1997;96 (suppl):1–66.

Pearson TA, McBride PE, Houston-Miller N, Smith SC Jr. Organization of preventive cardiology service. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:1035–47.

Kottke TE, Blackburn H, Brekke ML, Solberg LI. Making time for preventive services. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68:785–91.

Smedire NG, Evans BH, Grais LS, et al. Withholding and withdrawal of life support from the critically ill. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:309–15.

Hanson LC, Danis M. Use of life-sustaining care for the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:772–7.

Fontana SA, Baumann LC, Helberg C, Love RR. The delivery of preventive services in primary care practices according to chronic disease status. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1190–6.

Redelmeier DA, Tan SH, Booth GL. The treatment of unrelated disorders in patients with chronic medical diseases. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1516–20.

Berwick DM. Payment by capitation and the quality of care. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1227–31.

Emanuel EJ, Dubler NN. Preserving the physician-patient relationship in the era of managed care. JAMA. 1995;273:323–9.

Avorn J, Monette J, Lacour A, et al. Persistence of use of lipid-lowering medications. JAMA. 1998;279:1458–62.

Andrade SE, Walker AM, Gottlieb LK, et al. Discontinuation of antihyperlipidemic drugs—do rates reported in clinical trials reflect rates in primary care settings? N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1125–31.

Sacks FM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, et al. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1001–9.

LIPID Study Group. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1349–57.

Kannel WB. Preventive efficacy of nutritional counseling. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1138–9.

Hunninghake DB, Stein EA, Dujovne CA, et al. The efficacy of intensive dietary therapy alone or combined with lovastatin in outpatients with hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1213–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (AG14474), the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (HSO7357), the Healthcare Education and Research Foundation, and the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Foundation. Dr. Majumdar was the recipient of a National Research Service Award (PE 11001-10).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Majumdar, S.R., Gurwitz, J.H. & Soumerai, S.B. Undertreatment of hyperlipidemia in the secondary prevention of coronary artery disease. J GEN INTERN MED 14, 711–717 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.02229.x

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.02229.x