Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To evaluate an innovative approach to continuing medical education, an outreach intervention designed to improve performance rates of breast cancer screening through implementation of office systems in community primary care practices.

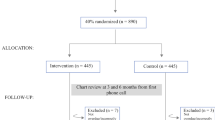

DESIGN: Randomized, controlled trial with primary care practices assigned to either the intervention group or control group, with the practice as the unit of analysis.

SETTING: Twenty mostly rural counties in North Carolina.

PARTICIPANTS: Physicians and staff of 62 randomly selected family medicine and general internal medicine practices, primarily fee-for-service, half group practices and half solo practitioners.

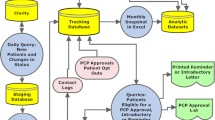

INTERVENTION: Physician investigators and facilitators met with practice physicians and staff over a period of 12 to 18 months to provide feedback on breast cancer screening performance, and to assist these primary care practices in developing office systems tailored to increase breast cancer screening.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS: Physician questionnaires were obtained at baseline and follow-up to assess the presence of five indicators of an office system. Three of the five indicators of office systems increased significantly more in intervention practices than in control practices, but the mean number of indicators in intervention practices at follow-up was only 2.8 out of 5. Cross-sectional reviews of randomly chosen medical records of eligible women patients aged 50 years and over were done at baseline (n=2,887) and follow-up (n=2,874) to determine whether clinical breast examinations and mammography, were performed. Results for mammography were recorded in two ways, mention of the test in the visit note and actual report of the test in the medical record. These reviews showed an increase from 39% to 51% in mention of mammography in intervention practices, compared with an increase from 41% to 44% in control practices (p=.01). There was no significant difference, however, between the two groups in change in mammograms reported (intervention group increased from 28% to 32.7%; control group increased from 30.6% to 34.0%, p=.56). There was a nonsignificant trend (p=.06) toward a greater increase in performance of clinical breast examination in intervention versus control practices.

CONCLUSIONS: A moderately intensive outreach intervention to increase rates of breast cancer screening through the development of office systems was modestly successful in increasing indicators of office systems and in documenting mention of mammography, but had little impact on actual performance of breast cancer screening. At follow-up, few practices had a complete office system for breast cancer screening. Outreach approaches to assist primary care practices implement office systems are promising but need further development.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Fletcher SW, Harris RP, Gonzalez JJ, et al. Increasing mammography utilization: a controlled study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85: 112–20.

Breen N, Kessler L. Changes in the use of screening mammography: evidence from the 1987 and 1990 National Health Interview Surveys. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:62–7.

Centers For Disease Control. Use of mammography services by women aged ≥ 65 years enrolled in Medicare—United States, 1991–1993. MMWR. 1995;44:777–81.

Kottke TE, Brekke ML, Solberg LI. Making “time” for preventive services. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68:785–91.

Jaen CR, Stange KC, Nutting PA. Competing demands of primary care: a model for the delivery of clinical preventive services. J Fam Pract. 1994;38:166–71.

Belcher DW, Berg AO, Inui TS. Practical approaches to providing better preventive care: are physicians a problem or solution. Am J Prev Med. 1988;4(suppl):27–48.

Davis DA, Thomson MA, Oxman AD, Haynes RB. Evidence for the effectiveness of CME: a review of 50 randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 1992;268:1111–7.

NCI Breast Cancer Screening Consortium. Screening mammography: a missed clinical opportunity? JAMA. 1990;264:54–8.

Dietrich AJ, Duhamel M. Improving geriatric preventive care through a patient-held checklist. Fam Med. 1989;21:195–8.

Dickey LL, Petitti D. A patient-held minirecord to promote adult preventive care. J Fam Pract. 1992;34:457–63.

Margolis KL, Menart TC. A test of two interventions to improve compliance with scheduled mammography appointments. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:539–41.

McPhee SJ, Detmer W. Office-based interventions to improve delivery of cancer prevention services by primary care physicians. Cancer. 1993;72:1100–2.

Gann P, Melville SK, Luckmann R. Characteristics of primary care office systems as predictor of mammography utilization. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:893–8.

Dietrich AJ, O’Connor GT, Keller A, Carney PA, Levy D, Whaley FS. Cancer: improving early detection and prevention: a community practice randomised trial. BMJ. 1992;304:687–91.

Leininger LS, Harris R, Jackson RS, Strecher VS, Kaluzny AD. CQI in primary care. In: McLaughlin CP, Kaluzny AD, eds. Continuous Quality Improvement in Health Care: Theory, Implementation, and Applications. Gaithersburg, Md: Aspen Publishers Inc.; 1994: Chap 14.

Leininger LS, Finn L, Dickey L, et al. An office system for organizing preventive services. A report by the American Cancer Society Advisory Group on Preventive Health Care Reminder Systems. Arch Fam Med. 1996;5:108–15.

Carney PA, Dietrich AJ, Keller A, Landgraf J, O’Connor GT. Tools, teamwork, and tenacity: an office system for cancer prevention. J Fam Pract. 1992;35:388–94.

Dickey LL, Kamerow DB. Primary care physicians’ use of office resources in the provision of prevention care. Arch Fam Med. 1996;5:399–404.

Lane DS, Burg MA. Promoting physician preventive practices: needs assessment for CME in breast cancer detection. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 1989;9:245–56.

Carey TS, Kinsinger LS, Keyserling T, Harris R. Research in the community: recruiting and retaining practices. J Community Health. 1996;21:315–27.

Kaluzny AD, Harris RP, Strecher VJ, Stearns S, Qaqish B, Leininger L. Prevention and early detection activities in primary care: new directions for implementation. Cancer Detect Prev. 1991;15:459–64.

Diggle PJ, Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Generalized estimating equations. In: Diggle PJ, Liang K-Y, Zeger SL, eds. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1994:151–2.

Lomas J, Enkin M, Anderson GM, Hannah WJ, Vayda E, Singer J. Opinion leaders vs audit and feedback to implement practice guidelines. JAMA. 1991;265:2202–7.

Greco PJ, Eisenberg JM. Changing physicians’ practices. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1271–4.

Moore DE, Green JS, Jay SJ, Leist JC, Maitland FM. Creating a new paradigm for CME: seizing opportunities within the health care revolution. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 1994;14:4–31.

Moore DE. Moving CME closer to the clinical encounter: the promise of quality management and CME. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 1995;15:135–45.

Frame PS, Zimmer JG, Werth PL, Martens WB. Description of a computerized health maintenance tracking system for primary care practice. Am J Prev Med. 1991;7:311–8.

Ornstein SM, Garr DR, Jenkins RG. A computerized microcomputer-based medical records system with sophisticated preventive services features for the family physician. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1993;6:55–60.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

This research was supported under grant CA 54343-02 from the National Cancer Institute.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kinsinger, L.S., Harris, R., Qaqish, B. et al. Using an office system intervention to increase breast cancer screening. J GEN INTERN MED 13, 507–514 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00160.x

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00160.x