ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

The three-item Brief Health Literacy Screen (BHLS) has been validated in research settings, but not in routine practice, administered by clinical personnel.

OBJECTIVE

As part of the Health Literacy Screening (HEALS) study, we evaluated psychometric properties of the BHLS to validate its administration by clinical nurses in both clinic and hospital settings.

PARTICIPANTS

Beginning in October 2010, nurses in clinics and the hospital at an academic medical center have administered the BHLS during patient intake and recorded responses in the electronic health record.

MEASURES

Trained research assistants (RAs) administered the short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (S-TOFHLA) and re-administered the BHLS to convenience samples of hospital and clinic patients. Analyses included tests of internal consistency reliability, inter-administrator reliability, and concurrent validity by comparing the nurse-administered versus RA-administered BHLS scores (BHLS-RN and BHLS-RA, respectively) to the S-TOFHLA.

KEY RESULTS

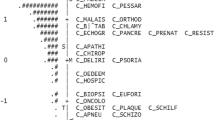

Cronbach’s alpha for the BHLS-RN was 0.80 among hospital patients (N = 498) and 0.76 among clinic patients (N = 295), indicating high internal consistency reliability. Intraclass correlation between the BHLS-RN and BHLS-RA among clinic patients was 0.77 (95 % CI 0.71–0.82) and 0.49 (95 % CI 0.40–0.58) among hospital patients. BHLS-RN scores correlated significantly with BHLS-RA scores (r = 0.33 among hospital patients; r = 0.62 among clinic patients), and with S-TOFHLA scores (r = 0.35 among both hospital and clinic patients), providing evidence of inter-administrator reliability and concurrent validity. In regression models, BHLS-RN scores were significant predictors of S-TOFHLA scores after adjustment for age, education, gender, and race. Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve for BHLS-RN to predict adequate health literacy on the S-TOFHLA was 0.71 in the hospital and 0.76 in the clinic.

CONCLUSIONS

The BHLS, administered by nurses during routine clinical care, demonstrates adequate reliability and validity to be used as a health literacy measure.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

Institute of Medicine. Health Literacy: A Prescrition to End Confusion. Washington: National Academies Press; 2004.

Kutner M GE, Jin Y, Boyle B, Hsu Y, Dunleavy E. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results From the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NCES 2006–483). Washington, DC; 2006.

Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:97–107.

Howard DH, Gazmararian J, Parker RM. The impact of low health literacy on the medical costs of Medicare managed care enrollees. Am J Med. 2005;118:371–377.

Eichler K, Wieser S, Brugger U. The costs of limited health literacy: a systematic review. Int J Public Health. 2009;54:313–324.

Kelly PA, Haidet P. Physician overestimation of patient literacy: a potential source of health care disparities. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66:119–122.

Powell CK, Kripalani S. Resident recognition of low literacy as a risk factor in hospital readmission. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:1042–1044.

Bass PF 3rd, Wilson JF, Griffith CH, Barnett DR. Residents’ ability to identify patients with poor literacy skills. Acad Med. 2002;77:1039–1041.

Sudore RL, Mehta KM, Simonsick EM, et al. Limited literacy in older people and disparities in health and healthcare access. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:770–776.

Paasche-Orlow MK, Schillinger D, Greene SM, Wagner EH. How health care systems can begin to address the challenge of limited literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:884–887.

Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS. Evidence does not support clinical screening of literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:100–102.

The Joint Commission. “What Did the Doctor Say?:” Improving Health Literacy to Protect Patient Safety. Available at http://www.jointcommission.org/What_Did_the_Doctor_Say/. Accessed June 10, 2013.

Davis TC, Crouch MA, Long SW, et al. Rapid assessment of literacy levels of adult primary care patients. Fam Med. 1991;23:433–435.

Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med. 1993;25:391–395.

Baker DW, Williams MV, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nurss J. Development of a brief test to measure functional health literacy. Patient Educ and Couns. 1999;38:33–42.

Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, Nurss JR. The test of functional health literacy in adults: a new instrument for measuring patients’ literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:537–541.

Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004;36:588–594.

Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, et al. Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:561–566.

Wallace LS, Cassada DC, Rogers ES, et al. Can screening items identify surgery patients at risk of limited health literacy? J Surg Res. 2007;140:208–213.

Wallace LS, Rogers ES, Roskos SE, Holiday DB, Weiss BD. Screening items to identify patients with limited health literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:874–877.

Sarkar U, Schillinger D, Lopez A, Sudore R. Validation of self-reported health literacy questions among diverse English and Spanish-speaking populations. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:265–271.

Cawthon C, Mion LC, Willens DE, Roumie CL, Kripalani S. Implementation of routine health literacy assessment in hospital and primary care patients. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2014 (in press).

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381.

McNaughton C, Wallston KA, Rothman RL, Marcovitz DE, Storrow AB. Short, subjective measures of numeracy and general health literacy in an adult emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18:1148–1155.

Chow GC. Tests of equality between sets of coefficients in two linear regressions. Econometrica. 1960;28:591–605.

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2000.

DeVellis RF. Scale Development: Theory and Applications. 2003.

Powers BJ, Trinh JV, Bosworth HB. Can this patient read and understand written health information? JAMA. 2010;304:76–84.

Baker DW. The meaning and the measure of health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:878–883.

Davis TC, Kennen EM, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV. Literacy testing in health care research. In: Schwartzberg JG, VanGeest JB, Wang CC, eds. Understanding Health Literacy. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2005:157–179.

Acknowledgements

Supported by R21 HL096581 and the Vanderbilt University Innovation and Discovery in Engineering And Science (IDEAS) Program Grant Award (Dr. Kripalani). Dr. Osborn is supported by a Career Development Award (K01 DK087894). Dr. McNaughton is supported by the Vanderbilt Emergency Medicine Research Training Program (K12 HL109019).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wallston, K.A., Cawthon, C., McNaughton, C.D. et al. Psychometric Properties of the Brief Health Literacy Screen in Clinical Practice. J GEN INTERN MED 29, 119–126 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2568-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2568-0