ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

As medical homes are developing under health reform, little is known regarding depression services need and use by diverse safety-net populations in under-resourced communities. For chronic conditions like depression, primary care services may face new opportunities to partner with diverse community service providers, such as those in social service and substance abuse centers, to support a collaborative care model of treating depression.

OBJECTIVE

To understand the distribution of need and current burden of services for depression in under-resourced, diverse communities in Los Angeles.

DESIGN

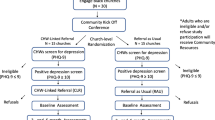

Baseline phase of a participatory trial to improve depression services with data from client screening and follow-up surveys.

PARTICIPANTS

Of 4,440 clients screened from 93 programs (primary care, mental health, substance abuse, homeless, social and other community services) in 50 agencies, 1,322 were depressed according to an eight-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8) and gave contact information; 1,246 enrolled and 981 completed surveys. Ninety-three programs, including 17 primary care/public health, 18 mental health, 20 substance abuse, ten homeless services, and 28 social/other community services, participated.

MAIN MEASURES

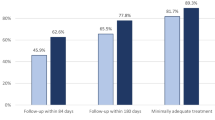

Comparisons by setting in 6-month retrospective recall of depression services use.

KEY RESULTS

Depression prevalence ranged from 51.9 % in mental health to 17.2 % in social-community programs. Depressed clients used two settings on average to receive depression services; 82 % used any setting. More clients preferred counseling over medication for depression treatment.

CONCLUSIONS

Need for depression care was high, and a broad range of agencies provide depression care. Although most participants had contact with primary care, most depression services occurred outside of primary care settings, emphasizing the need to coordinate and support the quality of community-based services across diverse community settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

Barry CL, Huskamp HA. Moving beyond parity — mental health and addiction care under the ACA. New Engl J Med. 2011;365(11):973–5.

Dietrich AJ, Oxman TE, Williams JW, Schulberg HC, Bruce ML, Lee PW, et al. Re-engineering systems for the treatment of depression in primary care: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2004;329(7466):602.

Burns B, Wagner H, Gaynes B, Wells K, Schulberg H. General medical and specialty mental health service use for major depression. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2000;30(2):127–43.

Wells KB, Sturm R, Sherbourn CD, Meredith LS. Caring for Depression. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1996.

Miranda J, Duan N, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Lagomasino I, Jackson-Triche M, et al. Improving care for minorities: can quality improvement interventions improve care and outcomes for depressed minorities? Results of a controlled randomized trial. Heal Serv Res. 2003;38(2):613–30.

Wells K, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Ettner S, Buan N, Miranda J, et al. Five-year impact of quality improvement for depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(4):378–86.

Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Duan N, Meredith L, Unutzer J, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283(2):212–20.

Hadley J, Cunningham P. Availability of safety net providers and access to care of uninsured persons. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(5):1527–46.

Galea S, Ahern J, Nandi A, Tracy M, Beard J, Vlahov D. Urban neighborhood poverty and the incidence of depression in a population-based cohort study. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(3):171–9.

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095–105.

Wang PS, Berglund PA, Kessler RC. Patterns and correlates of contacting clergy for mental disorders in the United States. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(2):647–73.

Williams DR, Gonzalez HM, Neighbors H, Nesse R, Abelson JM, Sweetman J, et al. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: results from the National Survey of American Life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(3):305–15.

Alegría M, Canino G, Ríos R, Vera M, Calderón J, Rusch D, et al. Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and non-Latino whites. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(12):1547–55.

Miranda J, Azocar F, Organista KC, Dwyer E, Areane P. Treatment of depression among impoverished primary care patients from ethnic minority groups. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(2):219–25.

Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):629.

Wang PS, Demler O, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Changing profiles of service sectors used for mental health care in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(7):1187.

Druss BG, Goldman HH. New Freedom Commission Report: introduction to the special section on the president’s New Freedom Commission Report. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(11):1465–6.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. In: Rosenthal RN, ed. Managing Depressive Symptoms in Substance Abuse Clients During Early Recovery: Treatment Improvement Protocol. Darby, PA: DIANE Publishing; 2008.

Institute of Medicine. Living Well with Chronic Illness: A Call for Public Action. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine of the National Academies; 2012.

Washington AE, Lipstein SH. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute - promoting better information, decisions, and health. New Engl J Med. 2011;365(15).

Israel BA, Coombe CM, Cheezum RR, Schulz AJ, McGranaghan RJ, Lichtenstein R, et al. Community-based participatory research: a capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2094.

Smedley BD, Syme SL. Promoting health: intervention strategies from social and behavioral research. National Academies Press; 2000.

Tunis SR, Stryer DB, Clancy CM. Practical clinical trials. JAMA. 2003;290(12):1624.

Bluthenthal R, Jones L, Fackler-Lowrie N, Ellison M, Booker T, Jones F, et al. Witness for wellness: preliminary findings from a community-academic participatory research mental health initiative. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(Suppl):S18–34.

Chung B, Jones L, Jones A, Corbett C, Booker T, Wells K, et al. Using community arts events to enhance collective efficacy and community engagement to address depression in an African American community. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(2):237.

Dobransky-Fasiska D, Nowalk M, Pincus H, Castillo E, Lee B, Walnoha A, et al. Public-academic partnerships: improving depression care for disadvantaged adults by partnering with non-mental health agencies. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(2):110.

Springgate BF, Allen C, Jones C, Lovera S, Meyers D, Campbell L, et al. Rapid community participatory assessment of health care in post-storm New Orleans. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(6):S237–S43.

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder. JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095–105.

Dwight Johnson M, Sherbourne CD, Liao D, Wells KB. Treatment preferences among depressed primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(8):527–34.

Chung B, Dixon EL, Miranda J, Wells K, Jones L. Using a community partnered participatory research approach to implement a randomized controlled trial: planning Community Partners in Care. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(3):780–95.

Katz DL, Murimi M, Gonzalez A, Njike V, Green LW. From controlled trial to community adoption: the Multisite Translational Community Trial. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(8).

Wells K, Jones L. Commentary: “research” in community-partnered, participatory research. JAMA. 2009;302(3):320–1.

Wells KB, Klap R, Fuentes S, Dossett E. Brief reports: obstacles and opportunities in providing mental health services through a faith-based network in Los Angeles. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(2):206–8.

Los Angeles County Department of Health Services. LA County Department of Health Services Key Health Indicators. Los Angeles, CA; 2009.

U.S. Census Bureau. United States Census 2000. Washington, D.C.; 2000.

Wells KB, Jones L, Chung B, Dixon E, Tang L, Gilmore J, et al. Community-Partnered Cluster-Randomized Comparative Effectiveness Trial of Community Engagement and Planning or Program Technical Assistance to Address Depression Disparities. Under review. 2012.

Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009;114(1–3):163–73.

Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF, Katz II, Schulberg HC, Mulsant BH, et al. Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients. JAMA. 2004;291(9):1081.

Datto CJ, Thompson R, Horowitz D, Disbot M, Oslin DW. The pilot study of a telephone disease management program for depression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003;25(3):169–77.

Unützer J, Katon W, Williams JW Jr, Callahan CM, Harpole L, Hunkeler EM, et al. Improving primary care for depression in late life: the design of a multicenter randomized trial. Medical Care. 2001;39(8):785.

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33.

RTI International. SUDAAN 10.0. Research Triangle Park, NC. 2012. http://www.rti.org/SUDAAN/. Accessed 04/18/2013.

Korn EL, Graubard BI. Analysis of Health Surveys. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley-Interscience; 1999.

Groves RM, Dillman D, Eltinge JL, Little RJA. Survey Nonresponse. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Interscience; 2002.

Little RJA. Missing-data adjustments in large surveys. J Bus Econ Stat. 1988;287–96.

Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Duan N, Meredith L, Unützer J, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care. JAMA. 2000;283(2):212.

Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponsive in Surveys. New York: Wiley; 1987.

Pyne JM, Rost KM, Zhang M, Williams DK, Smith J, Fortney J. Cost-effectiveness of a primary care depression intervention. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(6):432–41.

Rost K, Nutting PA, Smith J, Werner JJ. Designing and implementing a primary care intervention trial to improve the quality and outcome of care for major depression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2000;22(2):66–77.

Whooley MA, Stone B, Soghikian K. Randomized trial of case - finding for depression in elderly primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(5):293–300.

Katon W, VonKorff M, Lin E, Simon G, Walker E, Unützer J, et al. Stepped collaborative care for primary care patients with persistent symptoms of depression: a randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(12):1109–15.

Meredith L, Cheng W, Hickey S, Dwight-Johnson M. Factors associated with primary care clinicians’ choice of a watchful waiting approach to managing depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(1):72–8.

Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW, Hunkeler E, Harpole L, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2836.

Watkins KE, Hunter SB, Hepner KA, Paddock SM, de la Cruz E, Zhou AJ, et al. An effectiveness trial of group cognitive behavioral therapy for patients with persistent depressive symptoms in substance abuse treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(6):577.

Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody-Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;14(9):537–46.

Ell K, Xie B, Quon B, Quinn DI, Dwight-Johnson M, Lee PJ. Randomized controlled trial of collaborative care management of depression among low-income patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(27):4488–96.

Blumenthal DS, Smith SA, Majett CD, Alema-Mensah E. A trial of 3 interventions to promote colorectal cancer screening in African Americans. Cancer. 2010;116(4):922–9.

Siegel JM, Prelip ML, Erausquin JT, Kim SA. A worksite obesity intervention: results from a group-randomized trial. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(2):327.

Katzelnick DJ, Simon GE, Pearson SD, Manning WG, Helstad CP, Henk HJ, et al. Randomized trial of a depression management program in high utilizers of medical care. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(4):345.

Rollman BL, Belnap BH, LeMenager MS, Mazumdar S, Houck PR, Counihan PJ, et al. Telephone-delivered collaborative care for treating post-CABG depression a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302(19):2095–103.

Cordasco KM, Asch SM, Bell DS, Guterman JJ, Gross-Schulman S, Ramer L, et al. A low-literacy medication education tool for safety-net hospital patients. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(6):S209–S16.

Dick J, Clarke M, Van Zyl H, Daniels K. Primary health care nurses implement and evaluate a community outreach approach to health care in the South African agricultural sector. Int Nurs Rev. 2007;54(4):383–90.

Perry CL, Stigler MH, Arora M, Reddy KS. Prevention in translation: tobacco use prevention in India. Health Promot Pract. 2008;9(4):378–86.

Brook O, van Hout H, Nieuwenhuyse H, Heerdink E. Impact of coaching by community pharmacists on drug attitude of depressive primary care patients and acceptability to patients; a randomized controlled trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;13(1):1–9.

Patel V, Weiss HA, Chowdhary N, Naik S, Pednekar S, Chatterjee S, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention led by lay health counsellors for depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care in Goa, India (MANAS): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9758):18–31.

Wilson TE, Feldman J, King G, Coll B, Homel P, Browne R, et al. Hair salon stylists as breast cancer prevention lay health advisors for African American and Afro-Caribbean women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19(1):216–26.

Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. JAMA. 2007;297(4):407–10.

Acknowledgements

We thank the 25 participating agencies of the Council and their representatives: QueensCare Health and Faith Partnership; COPE Health Solutions; UCLA Center for Health Services and Society; Cal State University Dominquez Hills; RAND; Healthy African American Families II; Los Angeles Urban League; Los Angeles Christian Health Centers; Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health and West Central Mental Health Center; Homeless Outreach Program/Integrated Care System; National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) Urban Los Angeles; Behavioral Health Services, Inc.; Avalon Carver Community Center; USC Keck School of Medicine Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences; Kaiser Watts Counseling and Learning Center; People Assisting the Homeless; Children’s Bureau; Saban Free Clinic; New Vision Church of Jesus Christ; Jewish Family Services of Los Angeles; St. John’s Well Child and Family Center; Charles Drew University of Medicine and Science; City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks; To Help Everyone Clinic; QueensCare Family Clinics and the National Institute of Mental Health (funder). We thank the participating Los Angeles programs, their providers and staff, and the clients who participated. We thank the RAND Survey Research Group and trained community members who conducted client data collection. We also thank Robert Brook and Jurgen Unutzer for helpful comments on earlier drafts.

Funding/Support

Community Partners in Care was funded by Award Numbers R01MENTAL HEALTH078853, P30MENTAL HEALTH082760, and P30MENTAL HEALTH068639 from the National Institute of Mental Health, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (64244). The content is the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the funders.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miranda, J., Ong, M.K., Jones, L. et al. Community-Partnered Evaluation of Depression Services for Clients of Community-Based Agencies in Under-Resourced Communities in Los Angeles. J GEN INTERN MED 28, 1279–1287 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2480-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2480-7