ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Depression management can be challenging for primary care (PC) settings. While several evidence-based models exist for depression care, little is known about the relationships between PC practice characteristics, model characteristics, and the practice’s choices regarding model adoption.

OBJECTIVE

We examined three Veterans Affairs (VA)-endorsed depression care models and tested the relationships between theoretically-anchored measures of organizational readiness and implementation of the models in VA PC clinics.

DESIGN

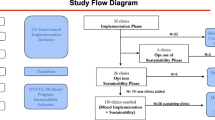

1) Qualitative assessment of the three VA-endorsed depression care models, 2) Cross-sectional survey of leaders from 225 VA medium-to-large PC practices, both in 2007.

MAIN MEASURES

We assessed PC readiness factors related to resource adequacy, motivation for change, staff attributes, and organizational climate. As outcomes, we measured implementation of one of the VA-endorsed models: collocation, Translating Initiatives in Depression into Effective Solutions (TIDES), and Behavioral Health Lab (BHL). We performed bivariate and, when possible, multivariate analyses of readiness factors for each model.

KEY RESULTS

Collocation is a relatively simple arrangement with a mental health specialist physically located in PC. TIDES and BHL are more complex; they use standardized assessments and care management based on evidence-based collaborative care principles, but with different organizational requirements. By 2007, 107 (47.5 %) clinics had implemented collocation, 39 (17.3 %) TIDES, and 17 (7.6 %) BHL. Having established quality improvement processes (OR 2.30, [1.36, 3.87], p = 0.002) or a depression clinician champion (OR 2.36, [1.14, 4.88], p = 0.02) was associated with collocation. Being located in a VA regional network that endorsed TIDES (OR 8.42, [3.69, 19.26], p < 0.001) was associated with TIDES implementation. The presence of psychologists or psychiatrists on PC staff, greater financial sufficiency, or greater spatial sufficiency was associated with BHL implementation.

CONCLUSIONS

Both readiness factors and characteristics of depression care models influence model adoption. Greater model simplicity may make collocation attractive within local quality improvement efforts. Dissemination through regional networks may be effective for more complex models such as TIDES.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

Kessler R, Chiu W, Demler O, Walters E. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of twelve-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Arch Gen Psychiat. 2005;62(6):617–27.

Singleton N, Bumpstead R, O’Brien M, Lee A, Meltzer H. Office of National Statistics: Psychiatric morbidity among adults living in private households, 2000. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office; 2001.

World Health Organization. Mental health: Depression. 2011; http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/definition/en/. Accessed August 21, 2012.

Simon G, Von Korff M. Recognition and management of depression in primary care. Arch Fam Med. 1995;4:99–105.

Young A, Klap R, Sherbourne C, Wells K. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2001;58(1):55–61.

Wang P, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus H, Wells K, Kessler R. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2005;62:629–40.

Alexopoulos G, Reynolds C, Bruce M, et al. Reducing suicidal ideation and depression in older primary care patients: 24-month outcomes of the PROSPECT study. Am J Psychiat. 2009;166:882–90.

Reiss-Brennan B, Briot P, Savitz L, Cannnon W, Staheli R. Cost and quality impact of Intermountain’s Mental Health Integration Program. J Healthc Manag. 2010;55(2):97–114.

Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan C, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2836–45.

Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Stepped collaborative care for primary care patients with persistent symptoms of depression: a randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiat. 1999;56(12):1109–15.

Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care. JAMA. 1995;273:1026–31.

Wells K, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al. Five-year impact of quality improvement for depression. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2001;61:378–86.

Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2314–21.

Bower P, Gilbody S, Richards D, Fletcher J, Sutton A. Collaborative care for depression in primary care. Br J Psychiat. 2006;189:484–93.

Simon GE, Katon WJ, VonKorff M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a collaborative care program for primary care patients with persistent depression. Am J Psychiat. 2001;158:1638–44.

Unutzer J, Katon WJ, Fan M-Y, et al. Long-term cost effects of collaborative care for late-life depression. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14:95–100.

Liu C-F, Hedrick SC, Chaney EF, et al. Cost-effectiveness of collaborative care for depression in a primary care veteran population. Psychiat Serv. 2003;54(5):698–704.

Lave J, Frank R, Schulberg H, Kamlet M. Cost-effectiveness of treatments for major depression in primary care practice. Arch Gen Psychiat. 1998;55:645–51.

Schoenbaum M, Unutzer J, Sherbourne C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of practice-initiated quality improvement for depression: results of a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;286(11):1325–30.

Nutting P, Rost K, Dickinson M, et al. Barriers to initiating depression treatment in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:103–11.

Henke R, McGuire T, Zaslavsky A, Ford D, Meredity L, Arbelaez J. Clinician- and organization-level factors in the adoption of evidence-based care for depression in primary care. Health Care Manag Rev. 2008;33(4):289–99.

Nutting P, Gallagher K, Riley K, et al. Care management for depression in primary care practice: findings from the RESPECT-depression trial. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:30–7.

Kilbourne A, Schulberg H, Post E, Rollman B, Belnap B, Pincus H. Translating evidence-based depression management services to community-based primary care practices. Milbank Q. 2004;82(4):631–59.

Belnap BH, Kuebler J, Upshur C, et al. Challenges of implementing depression care management in the primary care setting. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2006;33(1):65–75.

Scott WR. Innovation in medical care organizations: a synthetic review. Med Care Res Rev. 1990;47(165):165–92.

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in Service Organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82(2):581–629.

Weiner B, Amick H, Lee SD. Review: conceptualization and measurement of organizational readiness for change: a review of the literature in health services research and other fields. Med Care Res Rev. 2008;65:379–436.

Hamilton AB, Cohen AN, Young AS. Organizational readiness in specialty mental health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;25(Suppl 1):27–31.

Lehman W, Greener J, Simpson D. Assessing organizational readiness for change. J Subst Abus Treat. 2002;22:197–209.

VHA Handbook 1160.01 Uniform Mental Health Services in VA Medical Centers and Clinics. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs: Office of Patient Care Services; 2008.

Rubenstein L, Meredith L, Parker L, et al. Impacts of evidence-based quality improvement on depression in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:1027–35.

Rubenstein L, Chaney E, Ober S, et al. Using evidence-based quality improvement methods for translating depression collaborative care research into practice. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28:91–113.

Zanjani F, Miller B, Turiano N, Ross J, Oslin D. Effectiveness of telephone-based referral care management, a brief intervention to improve psychiatric treatment engagement. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:776–81.

Oslin D, Ross J, Sayers S, Murphy J, Kane V, Katz I. Screening, assessment, and management of depression in VA primary care clinics: The Behavioral Health Laboratory. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:46–50.

Oslin D, Sayers S, Ross J, et al. Disease management for depression and at-risk drinking via telephone in an older population of veterans. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(6):931–7.

Liu C-F, Rubenstein LV, Kirchner JE, et al. Organizational cost of quality improvement for Depression Care. Heal Serv Res. 2009;44(1):225–44.

Rubenstein LV, Jackson-Triche M, Unutzer J, et al. Evidence-based care for depression in managed primary care practices. Heal Aff. 1999;18(5):89–105.

Post EP, Kilbourne AM, Bremer RW, Solano FX, Jr, Pincus HA, Reynolds CF, III. Organizational factors and depression management in community-based primary care settings. Implement Sci. 2009;4:84.

Tew J, Klaus J, Oslin D. The behavioral health laboratory: building a stronger foundation for the Patient-centered medical home. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28(2):130–45.

Thielke S, Vannoy S, Unutzer J. Integrating mental health and primary care. Prim Care Clin Office Pract. 2007;34:571–92.

Bower P, Knowles S, Coventry PA, Rowland N. Counselling for mental health and psychosocial problems in primary care (Review). Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2011(9).

Krahn DD, Bartels SJ, Coakley E, et al. PRISM-E: comparison of integrated care and enhanced specialty referral models in depression outcomes. Psychiat Serv. 2006;57(7):946–53.

Simpson D. A conceptual framework for transferring research to practice. J Subst Abus Treat. 2002;22:171–82.

Rogers E. Diffusion of innovations. New York: The Free Press; 1995.

Yano E, Fleming B, Canelo, et al. National Survey Results for the Primary Care Director Module of the VHA Clinical Practice Organizational Survey. Sepulveda, CA: VA HSR&D Center for the Study of Healthcare Provider Behavior; 2008.

Chou A, Rose D, Farmer M, Canelo I, Rubenstein L, Yano E. Organizational Factors Affecting the Likelihood of CancerScreening among VA Patients. Paper presented at: 13th Annual Healthcare Organizational Research Association (HORA) ConferenceJune 2011; Seattle, WA.

Kline R. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: The Guilford Press; 2005.

Groves R, Fowler F Jr, Couper M, Lepkowski J, Singer E, Tourangeau R. Survey methodology. 2nd ed. Hoboken: Wiley; 2009.

Area Resource File (ARF). Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professions; 2008.

Department of Veterans Affairs. Office of Academic Affiliations. http://www.va.gov/oaa/. Accessed Aug 21, 2012.

Agresti A, Franklin C. Statistics: The art and science of learning from data. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2009.

Wagner E, Austin B, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schafer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Heal Aff. 2001;20(6):64–78.

Improving Chronic Illness Care. 1996-2012; The MacColl Center. The Improving Chronic Illness Care program is supported by The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, with direction and technical assistance provided by Group Health’s MacColl Center for Health Care Innovation. Available at: http://www.improvingchroniccare.org/. Accessed Aug 21, 2012.

Pomerantz A, Shiner B, Watts B, et al. The White River Model of colocated collaborative care. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28(2):114–29.

Pomerantz AS, Cole BH, Watts BV, Weeks WB. Improving efficiency and access to mental health care: combining integrated care and advanced clinical access. Gen Hosp Psychiat. 2008;30:546–51.

Pomerantz A, Sayers S. Primary care-mental health integration in healthcare in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28(2):78–82.

Watts B, Shiner B, Pomerantz A, Stender P, Weeks W. Outcomes of a quality improvement project integrating mental health into primary care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16:378–81.

Parker V, Wubbenhorst W, Young G, Desai KR, Charns MP. Implementing quality improvement in hospitals: the role of leadership and culture. Am J Med Qual. 1999;14:64–9.

Hemmelgarn A, Glisson C, James L. Organizational culture and climate: implications for services and interventions research. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2006;13(1):73–89.

Shortell S, O’Brien J, Carman J, et al. Assessing the impact of continuous quality improvement/total quality management: concept vs implementation. Heal Serv Res. 1995;30(2):377–401.

Collaborative Care for Depression in the Primary Care Setting: a primer on VA’s Translating Initiatives for Depression into Effective Solutions (TIDES) Project. In: VA Health Services Research and Development Service, Office of Research and Development, Dept of Veterans Affairs, ed. Washington, DC 2008.

Acknowledgements

Contributors

Contributors include Steven Asch, MD MPH, Ann Chou, PhD, Johanna Klaus, PhD, Edmund Chaney, PhD, John McCarthy, PhD, Michael Mitchell, PhD, Susan Stockdale, PhD, and Brian Mittman, PhD.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs, or the US government, or other affiliated institutions.

Funders

Funding support provided by VA Office of Academic Affiliations, Health Services Research and Development through the Health Services Fellowship Training Program (TMP 65-020). Dr. Yano’s time was funded by the VA HSR&D Service through a Research Career Scientist Award (Project # RCS 05-195). The project was also supported by VA HSR&D Project #09-082 (Yano, PI).

Prior Presentations

Oral abstracts summarizing these findings were presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine 35th Annual Meeting on May 9-12, 2012 in Orlando, Florida, and the Academy Health Annual Research Meeting on June 25–27, 2012 in Orlando, Florida.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(PDF 62 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, E.T., Rose, D.E., Yano, E.M. et al. Determinants of Readiness for Primary Care-Mental Health Integration (PC-MHI) in the VA Health Care System. J GEN INTERN MED 28, 353–362 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2217-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2217-z