ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Although collaborative care is effective for treating depression and other mental disorders in primary care, there have been no randomized trials of collaborative care specifically for patients with Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

OBJECTIVE

To compare a collaborative approach, the Three Component Model (3CM), with usual care for treating PTSD in primary care.

DESIGN

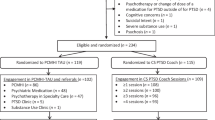

The study was a two-arm, parallel randomized clinical trial. PTSD patients were recruited from five primary care clinics at four Veterans Affairs healthcare facilities and randomized to receive usual care or usual care plus 3CM. Blinded assessors collected data at baseline and 3-month and 6-month follow-up.

PARTICIPANTS

Participants were 195 Veterans. Their average age was 45 years, 91% were male, 58% were white, 40% served in Iraq or Afghanistan, and 42% served in Vietnam.

INTERVENTION

All participants received usual care. Participants assigned to 3CM also received telephone care management. Care managers received supervision from a psychiatrist.

MAIN MEASURES

PTSD symptom severity was the primary outcome. Depression, functioning, perceived quality of care, utilization, and costs were secondary outcomes.

KEY RESULTS

There were no differences between 3CM and usual care in symptoms or functioning. Participants assigned to 3CM were more likely to have a mental health visit, fill an antidepressant prescription, and have adequate antidepressant refills. 3CM participants also had more mental health visits and higher outpatient pharmacy costs.

CONCLUSIONS

Results suggest the need for careful examination of the way that collaborative care models are implemented for treating PTSD, and for additional supports to encourage primary care providers to manage PTSD.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–27.

Magruder KM, Frueh BC, Knapp RG, et al. Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in Veterans Affairs primary care clinics. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27:169–79.

Schnurr PP, Green BL, eds. Trauma and Health: Physical Health Consequences of Exposure to Extreme Stress. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2004.

National Comorbidity Survey-Replication. Lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV/WMH-CIDI disorders by sex and cohort. Available at: http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/ftpdir/NCS-R_Lifetime_Prevalence_Estimates.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2012.

Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, et al. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. New Engl J Med. 2004;351:13–22.

Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Rosenheck RA. Combat trauma: trauma with highest risk of delayed onset and unresolved posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, unemployment, and abuse among men. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189:99–108.

Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Posttraumatic Stress. http://www.healthquality.va.gov/Post_Traumatic_Stress_Disorder_PTSD.asp. Accessed June 22, 2012.

Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, Cohen JA. Effective treatments for PTSD. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 2008.

Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, et al. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:603–13.

Liebschutz J, Saitz R, Brower V, et al. PTSD in urban primary care: high prevalence and low physician recognition. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:719–26.

Meredith LS, Eisenmann DP, Green BL, et al. System factors affect the recognition and management of posttraumatic stress disorder by primary care clinicians. Med Care. 2009;47:686–94.

Possemato K, Ouimette P, Lantinga LA, et al. Treatment of Department of Veterans Affairs primary care patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Serv. 2011;8:82–93.

Mohammed S, Rosenheck R. Pharmacotherapy for older veterans diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder in Veterans Administration. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:804–12.

Possemato K. The current state of intervention research for posttraumatic stress disorder within the primary care setting. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2011;18:268–80.

Zatzick D, Roy-Byrne P, Russo J, et al. Collaborative interventions for physically injured trauma survivors: a pilot randomized effectiveness trial. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23:114–23.

Zatzick D, Roy-Byrne P, Russo J, et al. A randomized effectiveness trial of stepped collaborative care for acutely injured trauma survivors. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:498–506.

Hegel M, Unützer J, Tang L, et al. Impact of comorbid panic and posttraumatic stress disorder on outcomes of collaborative care for late-life depression in primary care. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:48–58.

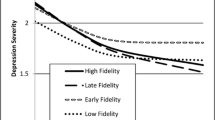

Chan D, Fan M-Y, Unützer J. Long-term effectiveness of collaborative depression care in older primary care patients with and without PTSD symptoms. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:758–64.

Craske MG, Stein MB, Sullivan G, et al. Disorder-specific impact of coordinated anxiety learning and management treatment for anxiety disorder in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:378–88.

Post EP, Metzger M, Dumas P, et al. Integrating mental health into primary care within the Veterans Health Administration. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28:83–90.

Bower P, Gilbody S, Richard D, et al. Collaborative care for depression in primary care: making sense of a complex intervention: systematic review and meta-regression. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:484–93.

Williams J, Gerrity M, Holsinger T, et al. Systematic review of multifaceted interventions to improve depression care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:91–116.

Oxman TE, Dietrich AJ, Williams JW, et al. A three-component model for reengineering systems for the treatment of depression in primary care. Psychosomatics. 2002;43:441–50.

Dietrich AJ, Oxman TE, Williams JW, et al. Re-engineering systems for the treatment of depression in primary care: cluster randomized controlled trial. Br Med J. 2004;329:602–5.

Engel CC, Oxman T, Yamamoto C, et al. RESPECT-Mil: feasibility of a systems-level collaborative care approach to depression and posttraumatic stress disorder in military primary care. Mil Med. 2008;173:935–40.

Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2836–45.

Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Int J Meth Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13.

Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, et al. Six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med Care. 2002;40:771–81.

Bradley KA, Kivlahan DR, Zhou XH, et al. Using alcohol screening results and treatment history to assess the severity of at-risk drinking in Veterans Affairs primary care patients. Alc Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:448–55.

Skinner H. The Drug Abuse Screening Test. Add Beh. 1982;7:363–71.

Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, et al. PTSD Checklist: reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. In: Proceedings of the 9th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS). Chicago, Ill: ISTSS; 1993:8.

Foa EB, Cashman L, Jaycox L, et al. The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale. Psychol Assess. 1997;9:445–51.

Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Covi L. SCL-90: an outpatient psychiatric rating scale – preliminary report. Psychopharm Bull. 1973;9:13–28.

Seal KH, Maguen S, Cohen B, et al. VA mental health services utilization in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in the first year of receiving new mental health diagnoses. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23:5–16.

Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK, et al. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries: results from the IQOLA Project. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1171–8.

Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R, et al. The Primary Care PTSD Screen (PC-PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Prim Care Phys. 2003;9:9–14.

Gilbody S, Bower P, Torgerson D, et al. Cluster randomized trials produced similar results to individually randomized trials in a meta-analysis of enhanced care for depression. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:160–8.

Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ, Foy DW, et al. A randomized trial of trauma focus group therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: results from a Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:481–9.

Oxman TE, Schulberg HC, Greenberg RL, et al. A fidelity measure for integrated management of depression in primary care. Med Care. 2006;44:1030–7.

van Buuren S, Oudshoorn K. MICE: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Statistical Software, in press.

Bradley RG, Greene J, Russ E, et al. A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy for PTSD. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:214–27.

Campbell DG, Felker BL, Liu C-F, et al. Prevalence of depression-PTSD comorbidity: implications for clinical practice guidelines and primary care-based interventions. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:711–8.

Chan D, Cheadle AD, Reiber G, et al. Health care utilization and its costs for depressed veterans with and without comorbid PTSD symptoms. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1612–7.

Friedman MJ, Marmar CR, Baker DG, et al. Randomized, double-blind comparison of sertraline and placebo for posttraumatic stress disorder in a Department of Veterans Affairs setting. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:711–20.

Zatzick D, Rivara F, Jurkovich G, et al. Enhancing the population impact of collaborative care interventions: mixed method development and implementation of stepped care targeting posttraumatic stress disorder and related comorbidities after acute trauma. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33:123–34.

Cigrang JA, Rauch SAM, Avila LL, et al. Treatment of active-duty military with PTSD in primary care: early findings. Psychol Serv. 2011;8:104–13.

Nutting PA, Gallacher KM, Riley K, et al. Implementing a depression improvement intervention in five health care organizations: experience from the RESPECT-Depression trial. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2007;34:127–37.

Gerrity MS, Williams JW, Dietrich AJ, et al. Identifying physicians likely to benefit for depression education: a challenge for health care organizations. Med Care. 2001;39:856–66.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the VA Health Services Research and Development Service. However, the views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or any US government agency.

We wish to thank the Site Principal Investigators Dzung V. Le, DO, Praveen Mehta, MD, Guna Raj, MD, Immanuel Thamban, MD, and Edwin Woo, MD and research staff (David S. Greenawalt, PhD, Kathy McNair, RN, Lisa D. Jones, Reed J. Robinson, PhD, Jack Y. Tsan, PhD, and Elizabeth S. Wiley, PhD). We also wish to thank Shelia Barry, Allison Brandt, MBA, Shuo Chen, PhD, Suzy B. Gulliver, PhD, Kathryn Kotrla, MD, Carol S. North, MD, Jeffrey Smith, PhD, John Williams, MD, Keith A. Young, PhD, and Yinong Young-Xu, DSc, for valuable assistance in planning or in implementing the study, and Charles C. Engel, MD for helpful discussions about the study findings.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Schnurr has provided consultation and content development on PTSD for Medscape. Oxman & Dietrich are partners in 3CM, LLC, a consultant group based on their work for the MacArthur Foundation in order to disseminate their work on integrating mental health in primary care. They primarily work with the U.S. Army, but have also worked with Aetna, the University of Miami and the New York City Dept. of Health and Mental Hygiene. Dr. Smith is employed by Thomson Reuters. All other authors have no conflicts to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Trial Registration

Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier NCT00373698

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schnurr, P.P., Friedman, M.J., Oxman, T.E. et al. RESPECT-PTSD: Re-Engineering Systems for the Primary Care Treatment of PTSD, A Randomized Controlled Trial. J GEN INTERN MED 28, 32–40 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2166-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2166-6