Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To systematically review the literature to determine which interventions improve the screening, diagnosis or treatment of cervical cancer for racial and/or ethnic minorities.

DATA SOURCES

Medline on OVID, Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials, CINAHL, PsycINFO and Cochrane Systematic Reviews.

STUDY ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA, PARTICIPANTS AND INTERVENTIONS

We searched the above databases for original articles published in English with at least one intervention designed to improve cervical cancer prevention, screening, diagnosis or treatment that linked participants to the healthcare system; that focused on US racial and/or ethnic minority populations; and that measured health outcomes. Articles were reviewed to determine the population, intervention(s), and outcomes. Articles published through August 2010 were included.

STUDY APPRAISAL AND SYNTHESIS METHODS

One author rated the methodological quality of each of the included articles. The strength of evidence was assessed using the criteria developed by the GRADE Working Group.45,46

RESULTS

Thirty-one studies were included. The strength of evidence is moderate that telephone support with navigation increases the rate of screening for cervical cancer in Spanish- and English-speaking populations; low that education delivered by lay health educators with navigation increases the rate of screening for cervical cancer for Latinas, Chinese Americans and Vietnamese Americans; low that a single visit for screening for cervical cancer and follow up of an abnormal result improves the diagnosis and treatment of premalignant disease of the cervix for Latinas; and low that telephone counseling increases the diagnosis and treatment of premalignant lesions of the cervix for African Americans.

LIMITATIONS

Studies that did not focus on racial and/or ethnic minority populations may have been excluded. In addition, this review excluded interventions that did not link racial and ethnic minorities to the health care system. While inclusion of these studies may have altered our findings, they were outside the scope of our review.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS OF KEY FINDINGS

Patient navigation with telephone support or education may be effective at improving screening, diagnosis, and treatment among racial and ethnic minorities. Research is needed to determine the applicability of the findings beyond the populations studied.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Though cervical cancer is a preventable illness, US women continue to develop this disease and to die from it. In 2011, 12,710 US women were expected to be diagnosed with and 4290 women to die from cervical cancer.1 The burden of cervical cancer is not shared equally among women of all races and ethnicities. While the age-adjusted incidence rate of cervical cancer for all US women is 8.1 per 100,000 women per year,1 Latinas have a significantly higher incidence of cervical cancer (11.1 per 100,000 women), as do African-American women (10.0 per 100,000).2 The incidence is five times higher among Vietnamese American women than white women.3

In addition, the mortality from cervical cancer is higher for African-American women (4.4 per 100,000 women), Latinas (3.1 per 100,000), and Native Americans/Native Alaskans (3.4 per 100,000), than it is for whites (2.2 per 100,000) and Asians/Pacific Islanders (2.1 per 100,000).1,4–6 Mortality from cervical cancer shows geographic variation in the US, with higher mortality rates among African-Americans in the Deep South, Latinas on the Texas-Mexico border, white women in Appalachia, rural New York State and northern New England, Native Americans living in the Northern Plains, and Native Alaskans.3 The mortality rate among foreign-born women is increasing, especially in the South.3

Because premalignant cervical disease progresses slowly to malignancy and is easily detected and treated, the continued existence of cervical cancer and the disparities in cervical cancer rates in the US are concerning. Human papillomavirus (HPV), a sexually transmitted infection, is implicated as the cause of almost all cervical cancer worldwide, so interventions that promote safe sexual practices and HPV vaccination should theoretically eliminate the incidence of cervical cancer.7 In addition, because the Papanicolaou (Pap) smear is a safe, low cost and relatively noninvasive screening test for cervical cancer, interventions targeted at increasing screening uptake and promotion of follow-up after abnormal screening should decrease the incidence of cervical cancer as well. Finally, because members of different racial and ethnic groups tend to achieve similar outcomes when they receive similar treatment, interventions that promote equal care and treatment should decrease mortality from cervical cancer.8

Unfortunately, the continued existence of cervical cancer and the disparities noted in its incidence and mortality suggest that these interventions have not been wholly successful. Among those newly diagnosed with cervical cancer, 30–60 % have never had a screening test.47,48 Up to 15 % have had inadequate follow up after an abnormal Pap smear.48 Sixty to eighty percent of women diagnosed with advanced cervical cancer have not had a screening test within the past 5 years.49,50 Interventions that maximize the prevention, screening, diagnosis or treatment of cervical cancer are critical to eradicate this disease. Currently, there exists no consolidated evaluation of the intervention research literature to determine which interventions improve cervical cancer prevention, screening, diagnosis or treatment for racial or ethnic minorities in the US. The purpose of this systematic review is to fill that gap.

METHODS

Data Sources and Searches

We conducted a systematic review of the English language literature to assess studies that described and evaluated interventions with the potential to improve cervical cancer prevention, screening, diagnosis or treatment for racial and/or ethnic minorities in the United States. We conducted an electronic search of the following five databases from their inception through August 2010: MEDLINE on OVID, The Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Systematic Reviews. We used an identical search strategy for each database (see Text Box 1). In addition, we searched the reference sections of relevant review articles as well as all included studies for additional manuscripts. This review does not have a published protocol and therefore, was not registered.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

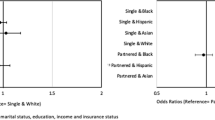

Titles and abstracts were reviewed by one author to determine eligibility for inclusion. Eligible studies had to meet all five inclusion criteria: 1) represent an original study; 2) include at least one intervention designed to improve cervical cancer prevention, screening, diagnosis or treatment that linked participants to the healthcare system; 3) present data for racial and/or ethnic minority populations in the US; 4) measure direct outcomes such as HPV vaccination (cervical cancer prevention), Pap tests (cervical cancer screening), follow up of abnormal Pap smears (cervical cancer diagnosis or treatment of premalignant disease of the cervix) or treatment of cervical cancer; and 5) report findings in English. We did not include conference abstracts or unpublished studies. Articles not meeting inclusion criteria were reviewed by a second author. When possible, disagreements were resolved by discussion; when this was not possible, a third author evaluated the title and abstract. Articles not recommended for exclusion were then reviewed in full. Following full text review, those articles that did not meet all five inclusion criteria were excluded from further review using the process described above for the title and abstract review. Figure 1 summarizes the literature search and data selection process.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

We reviewed the included articles to determine the population, intervention(s) outcomes, study design and sample size. We did not contact authors about the possibility of unpublished subgroup analyses. One author rated the methodological quality of each of the included articles using a modified scoring algorithm based on criteria developed by Downs and Black (DB).9 To describe the risk of methodological bias for each study, we added one item from the Cochrane Collaboration tool10 to the DB tool, resulting in a maximum modified DB score of 29. Articles with a DB score >20 have been found to be of very good quality, those with scores 15–19 are of good quality, 11–14 of fair quality and <10 of poor quality.43 A second author conducted a 23 % re-review of publications; the interrater Pearson’s correlation coefficient was .97.

To determine the effect of each type of intervention, we classified studies by intervention type. Because most intervention strategies consisted of more than one intervention, we also grouped studies with similar intervention components together to determine the effect of the combination of interventions. We evaluated the strength of evidence for individual interventions and for groups of similar interventions using the criteria developed by the GRADE Working Group.45,46 This system utilizes four domains (bias, consistency, directness, and precision) to assess the strength of evidence as high, moderate, low, or insufficient.

RESULTS

Search Results

After removal of duplicates, the electronic search of the five databases yielded 2371 articles (Fig. 1). Following title and abstract review, we excluded 2192 articles for failure to meet one of the inclusion criteria, leaving 179 articles for full text review. Following full text review, 149 articles did not meet one or more of the inclusion criteria and were excluded; 21 of these studies were excluded due to lack of linkage to the health care setting. This left 30 intervention studies for detailed review. Review of the reference lists of relevant review articles and of all included studies identified one additional article for inclusion.31 Therefore, 31 studies were included in this systematic review.

Data Synthesis

Twenty-four studies described interventions to increase cervical cancer screening and six studies described interventions to improve the diagnosis and treatment of premalignant lesions of the cervix. One study described interventions both to increase screening for cervical cancer and to improve the diagnosis and treatment of malignant or premalignant lesions of the cervix.42 No studies described interventions to improve HPV vaccination.

Quality Assessment

Of the studies of interventions to improve screening for cervical cancer in racial and ethnic minority populations, one was of very good quality,14 ten were of good quality,15,22,23,32–36,39,40 12 were of fair quality,12,13,16–21,25,37,38,41 and one was of poor quality.26 Of the studies of interventions to improve the diagnosis and treatment of premalignant disease of the cervix, three were of good quality27–29 and three were of fair quality.24,30,31 The single study that included both types of interventions was of fair quality.42 The average modified DB score of included articles was 15 (range 9–23). In comparison, for a recent group of systematic reviews of interventions to reduce disparities, the average DB score was 18 out of a maximum score of 27 points.11

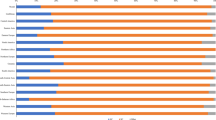

Types of Interventions Examined

Of the 25 studies evaluating interventions to improve the rate of screening for cervical cancer, eight included a single intervention12,17,32–34,38,40,42 and 17 included multiple interventions.13–16,18–23,25,26,35–37,39,41 The most common interventions were educational materials and education programs. Nineteen interventions included educational materials12,13,15,16,18–23,25,26,32,33,36,37,39–41 and 15 included education programs.15,16,18,19,21–23,25,26,35–37,39,41 Seven interventions included navigation (including assistance scheduling appointments, finding low-cost sources of care and with transportation),13–15,22,23,35,36 five included strategies to provide low-cost screening,16,21,26,37,42 five included strategies to improve access to screening,17,18,21,34,38,39 four included reminders for healthcare providers,18–20,25,41 four included advertisements,22,25,26,39 four included office policies and procedures (such as protocols or tracking systems),18,25,26,41 three included telephone counseling or support,13,14,20 two included feedback for providers on screening rates,18,41 and one included upgraded equipment.18

Of the seven studies evaluating interventions to improve the diagnosis and treatment of premalignant disease of the cervix in minority populations, two involved telephone counseling.27,28 One study created a streamlined process for cervical cancer screening and follow up of abnormalities29; one included intensive follow up and/or vouchers for reduced-cost care30; and one included a personalized letter and pamphlet and/or an audiovisual presentation and/or transportation incentives.31 One study included written educational materials, education programs, and messages in the media24; and one evaluated the Breast and Cervical Cancer Prevention and Treatment Act of 2000, which authorized Medicaid expansion to cover treatment of patients screened under the Breast and Cervical Cancer Mortality Prevention Act and found to have an abnormal Pap smear.42

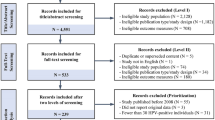

Impact of Interventions to Increase Screening

Of the eight studies that included a single intervention, four evaluated the effect of educational materials alone to increase the rate of screening for cervical cancer in minority populations.12,32,33,40 For two of these studies, the educational materials consisted of letters32,40; for the other two studies, the intervention consisted of videos.12,33 Overall, Jibaja–Weiss found an increase in the rate of screening for cervical cancer for patients who received a form letter (43.9 % form letter vs. 39.9 % control), though not for patients who received a tailored letter (23.7 % tailored letter vs. 39.9 % control).40 However, this difference was not statistically significant. After examining the findings by patient race and ethnicity, Jibaja–Weiss found a statistically significant decrease in the rate of screening for cervical cancer for African American, Mexican American and white women who received a tailored letter.32 While white women who received a form letter experienced increased odds of screening (OR 2.13, 95 % CI 1.13–4.03); African American and Mexican American patients did not (for African Americans, OR 0.96, 95 % CI 0.63–1.46; for Mexican Americans, OR 1.17, 95 % CI 0.78–1.76). Rivers found that when the Pap smear was described as detection behavior, a group of African American, Latino and white women were twice as likely to obtain a Pap smear when the message was loss-framed than when it was gain-framed (95 % CI 0.91–4.39).33 When the Pap smear was described as prevention behavior, women were no more likely to obtain a Pap smear when the message was gain-framed than when it was loss-framed (OR 1.14, 95 % CI 0.55–2.36).33 Yancey showed educational videos to a sample of low income African American, Latina and white women in a clinic waiting room. She found the proportion of women seen in the clinic receiving screening was higher during intervention weeks than during control weeks (clinic 1: 26.9 % intervention vs. 19.4 % control, p = 0.01; clinic 2 14.6 % intervention vs.10.3 % control, p = 0.02).12 Because of the inconsistent effect of the interventions, the strength of evidence that educational materials improve screening for cervical cancer in minority populations is insufficient (Tables 1 and 2).

Of the remaining four studies that addressed a single intervention to improve screening for cervical cancer in racial or ethnic minority populations,17,34,38,42 each evaluated the impact of a unique intervention. Margolis evaluated the impact of using lay health advisers to offer women due for screening an appointment with a female nurse practitioner.34 Because of the moderate risk of bias given this single study that utilized a quasi-experimental design and the lack of a statistically significant impact for minority populations, the strength of evidence is insufficient that offering women an appointment with a female nurse practitioner increases screening for cervical cancer in minority populations (see Tables 1 and 2). The fair or poor quality of the three other studies that addressed a single intervention to improve screening for cervical cancer in minority populations confers a high risk of bias. Therefore, the strength of evidence for these interventions is also insufficient (see Tables 1 and 2).

Of the studies that evaluated the impact of multiple interventions, five included education delivered by lay health workers plus navigation in combination with other interventions (educational materials and/or messages in the media), on the rate of screening for cervical cancer.15,22,23,35,36 Compared to control, all found an increase in the rate of screening for cervical cancer with the intervention. Wang found a 70 % rate of screening for cervical cancer with the intervention for Chinese American women compared to 11.1 % for the control condition (p < 0.001).23 Mock found increases in the rate of screening for cervical cancer for Vietnamese women in both intervention and control groups (intervention 65.8 % to 81.8 %, p < 0.001; control 70.1 % to 75.5 %, p < 0.001).22 The increase in the intervention group was significantly greater than that in the control (Z test p = 0.001).22 Fernandez found that 39.5 % of Latinas in the intervention group completed screening compared to 23.6 % in the control group (p < 0.05).36 However, intention to treat analysis showed no significant difference in the rate of screening.36 Taylor found an increase in Pap testing for Chinese women in the interval between randomization and the follow up survey (37 % vs. 22 %); however, this finding was not statistically significant.15 Jandorf also found an increase in the rate of Pap smear screening following the intervention for Latinas that was not statistically significant (51 % vs. 30 %, p = 0.0801).35 However, multivariate analysis revealed a statistically significant adjusted odds ratio of 3.9 for the effect of the intervention on adherence to screening (95 % CI 1.1–14.1).35 Because of the low risk of bias due to the presence of multiple good quality studies, the consistency of study findings, and the imprecise estimates of effect, the strength of evidence is low that education delivered by lay health educators together with navigation increases the rate of screening for cervical cancer for minority populations (Tables 1 and 2).

Two of the studies that evaluated the impact of multiple interventions on screening for cervical cancer examined the effect of navigation and telephone support.13,14 One of these studies also included written educational materials13; the other did not. Following the intervention, Dietrich found a 7 % increase in the proportion of women up to date for cervical cancer screening (95 % CI 0.03–0.11).14 Similarly, Beach found an increase in the up-to-date status for cervical cancer screening in the intervention group compared to the control group (adjusted odds ratio 1.73, 95 % CI 1.31–2.27).13 The benefit was greater for Spanish-speaking women than for English-speaking women (adjusted OR for Spanish-speaking women 2.18, 95 % CI 1.52–3.13; adjusted OR for English-speaking women 1.25, 95 % CI 0.81–1.91).13 Because of the low risk of bias due to one randomized controlled trial of very good quality, the consistency of study findings, and the precise estimate of effect, the strength of evidence is moderate that telephone support together with navigation increases the rate of screening for cervical cancer for minority populations (Tables 1 and 2).

The remaining studies that evaluated the impact of multiple interventions on screening for cervical cancer examined the effect of unique combinations of interventions.18–21,25,26,39,41 Due to the high risk of bias conferred by a single quasi-experimental study of good quality39 or a single study of fair or poor quality,16,18–21,25,26,37,41 the strength of evidence is insufficient that these combinations of interventions improve the rate of screening for cervical cancer in minority populations (Tables 1 and 2).

Interventions to Improve Diagnosis or Treatment

Of the seven studies that evaluated the impact of interventions to improve the diagnosis or treatment of premalignant disease of the cervix, four evaluated the impact of a single intervention27–29,42 and three evaluated the impact of a combination of interventions.24,30,31 In a randomized controlled trial, Brewster evaluated a single visit for both screening for cervical cancer and follow up of an abnormal result (High-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion (HGSIL), Atypical Glandular Cells of Uncertain Significance (AGUS) or carcinoma).29 She found that for women whose Pap smear revealed HGSIL/AGUS, 88 % in the intervention group were treated within six months of diagnosis compared to 53 % in the usual care group (p = 0.04).29 Because of the low risk of bias given the study design and quality for this single study, the direct measurement of outcomes, and the precision of the estimate, the strength of evidence is low that a single visit for screening for cervical cancer and follow up of an abnormal result results in improvement in the diagnosis and treatment of premalignant disease of the cervix in minority populations (Tables 3 and 4).

Two studies assessed the impact of telephone counseling on the diagnosis and treatment of premalignant disease of the cervix.27,28 Compared to the control group, Lerman found the odds of adherence to colposcopy were 2.6 times higher for the intervention group (p < 0.003).27 Miller found that compared to telephone appointment confirmation, telephone counseling resulted in increased adherence to the initial colposcopy appointment (76 % vs. 68 %, OR 1.50, 95 % CI 1.04–2.17), and for attendance at the six-month colposcopy appointment (61 % vs. 36 %, OR 2.70, 95 % CI 1.15–6.51).28 Given the moderate risk of bias due to one randomized controlled trial and one quasi-experimental study of good quality, the consistency of the findings, and the precision of the estimate, the strength of evidence is low that telephone counseling increases the diagnosis and treatment of premalignant lesions of the cervix for minority women (Tables 3 and 4).

One study evaluated the impact of Medicaid expansion to cover treatment for patients diagnosed with malignant or premalignant disease of the cervix through the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program.42 Due to the high risk of bias conferred by a single quasi-experimental study of fair quality and the lack of precision around the estimates, the strength of evidence is insufficient that this intervention improves the diagnosis or treatment of premalignant disease of the cervix in minority populations (Tables 3 and 4).

The three studies that evaluated the impact of multiple interventions on screening for cervical cancer examined the effect of unique combinations of interventions.24,30,31 Due to the high risk of bias conferred by a single quasi-experimental study of fair quality, the strength of evidence is insufficient that these combinations of interventions improve the diagnosis or treatment of premalignant disease of the cervix in minority populations.

DISCUSSION

Summary of Results

This systematic review found a moderate strength of evidence that telephone support with navigation increases the rate of screening for cervical cancer in minority populations. The strength of evidence is low that education delivered by lay health educators with navigation increases the rate of screening for cervical cancer in minority populations. For all of the other interventions and combinations of interventions studied, the strength of evidence is insufficient that these interventions improve the rate of screening for cervical cancer in minority populations.

This systematic review also found a low strength of evidence that a single visit for screening for cervical cancer and follow up of an abnormal result improves the diagnosis and treatment of premalignant disease of the cervix in minority populations. In addition, the strength of evidence is low that telephone counseling increases the diagnosis and treatment of premalignant lesions of the cervix for minority women. For all of the other interventions and combinations of interventions studied, the strength of evidence is insufficient that these interventions improve the diagnosis and treatment of premalignant lesions of the cervix for minority women.

Implications

For clinicians, administrators, policy makers and others striving to improve the rate of screening for cervical cancer in minority populations, telephone support with navigation and education programs by lay health educators with navigation may be of benefit. Telephone support with navigation has been shown to be effective for both Spanish-speaking and English-speaking populations.13,14 Education programs led by lay health educators together with navigation have been shown to be effective for Latina, Chinese and Vietnamese populations.22,23,36

A single visit for screening for cervical cancer and follow up of an abnormal result may improve the diagnosis and treatment of premalignant disease of the cervix for minority populations, as may telephone counseling. A single visit for screening and follow up was evaluated in a population that was predominantly Latina; therefore, its findings are most applicable to this group. Telephone counseling was evaluated in a population that was predominantly African American; therefore, its conclusions are directly applicable to this group.

Limitations of the Systematic Review Process

Our search strategy may have overlooked studies that reported data on racial and ethnic minorities, but did not focus on these population groups. However, we feel this is unlikely because our search identified studies that focused on populations other than racial or ethnic minorities, such as women attending a community health clinic or low-income women.

Because our aim was to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions that linked participants to the health care system, we deliberately excluded 21 studies that failed to do so. While it is possible that inclusion of these studies would have altered our findings, these studies were outside the scope of our systematic review.44

Though the original DB score has been validated and the use of DB to categorize studies qualitatively has been described,43 the use of this strategy to classify studies as very good, good, fair or poor has not yet been validated. Therefore, it is possible that we have misclassified some studies, especially those near the cut point for a qualitative score. However, because we were conservative in our estimate of risk of bias when determining the strength of evidence, if misclassification were to have affected our results, it would have biased our findings toward the null.

We neither searched for unpublished studies nor contacted authors about potential unpublished subgroup analyses. Thus, the results of our review may be influenced by publication bias and might bias our findings away from the null.

Recommendations for Future Research

While navigation seems a core element of the interventions that improve screening for cervical cancer in minority populations, there is insufficient evidence to determine whether navigation alone improves this outcome. Because a single intervention may be more easily implemented and less costly than one that includes multiple elements, it is important to determine whether navigation alone improves screening for cervical cancer, as well as the added costs and benefits of adding lay health education or telephone support. In addition, because the combination of navigation and education programs conducted by lay health educators have been inadequately studied in African Americans or Native Americans, future research should fill this gap. As navigation in conjunction with telephone support has been inadequately studied in populations that speak languages other than English or Spanish, further studies should confirm that this combination of interventions is effective in these populations.

Interventions with the potential to improve the diagnosis and treatment of premalignant lesions of the cervix are understudied. Future research should seek to extend the findings of the Brewster study29 to additional populations, especially African Americans, Asian Americans and Native Americans. In addition, future research should confirm the effect of telephone counseling in additional populations, notably Latinas, Asian Americans and Native Americans.

References

Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results. SEER Stat Fact Sheet: Cervix Uteri. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/cervix.html. Accessed March 8, 2012.

U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2007 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report. Atlanta (GA): Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and National Cancer Institute; 2010.

Freeman HP, Wingrove BK. Excess Cervical Cancer Mortality: A Marker for Low Access to Health Care in Poor Communities. Rockville, MD: National Cancer Institute, Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities, May 2005. NIH Pub. No. 05–5282.

Jemal A, et al. Cancer Statistics, 2004. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:30–40.

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures for Hispanics 2006–8. American Cancer Society 2006.

Howe HL, Wu X, Rus LA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2003, featuring cancer among US Hispanic/Latino populations. Cancer. 2006;107(8):1711–42.

Walbloomers JMM. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999;189(1):12–19.

Brawley O. Some perspective on black-white cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52:322–5.

Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomized and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52:377–384.

Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.2 [updated September 2009]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2009. Available at: www.cochrane-handbook.org. Accessed March 8, 2012.

Chin MH, Walters AE, Cook SC, Huang ES. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Finding Answers: Disparities Research for Change Systematic Review Leadership Team Health Disparities. Medical Care Research and Review: Special Supplemental Issue. 2007;64(5) supplement.

Yancey AK, Walden L. Stimulating cancer screening among Latinas and African-American women. A community case study. J Canc Educ. 1994;9(1):46–52.

Beach ML, Flood AB, Robinson CM, Cassells AN, Tobin JN, Greene MA, et al. Can language-concordant prevention care managers improve cancer screening rates? Canc Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(10):2058–64.

Dietrich AJ, Tobin JN, Cassells A, Robinson CM, Greene MA, Sox CH, et al. Telephone care management to improve cancer screening among low-income women: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(8):563–71.

Taylor VM, Hislop TG, Jackson JC, Tu S-P, Yasui Y, Schwartz SM, et al. A randomized controlled trial of interventions to promote cervical cancer screening among Chinese women in North America. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(9):670–7.

Whitman S, Lacey L, Ansell D, Dell J, Chen E, Phillips CW. An intervention to increase breast and cervical cancer screening in low-income African-American women. Fam Community Health. 1994;17(1):56–63.

Mandelblatt J, Traxler M, Lakin P, Thomas L, Chauhan P, Matseoane S, et al. A nurse practitioner intervention to increase breast and cervical cancer screening for poor, elderly black women. The Harlem Study Team. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8(4):173–8.

Bastani R, Berman BA, Belin TR, Crane LA, Marcus AC, Nasseri K, et al. Increasing cervical cancer screening among underserved women in a large urban county health system: can it be done? What does it take? Med Care. 2002;40(10):891–907.

Nguyen BH, Nguyen K, McPhee SJ, Nguyen AT, Tran DQ, Jenkins CNH. Promoting cancer prevention activities among Vietnamese physicians in California. J Canc Educ. 2000;15(2):82–5.

Rimer BK, Conaway M, Lyna P, Glassman B, Yarnall KS, Lipkus I, et al. The impact of tailored interventions on a community health center population. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;37(2):125–40.

Gotay CC, Banner RO, Matsunaga DS, Hedlund N, Enos R, Issell BF, et al. Impact of a culturally appropriate intervention on breast and cervical screening among native Hawaiian women. Prev Med. 2000;31(5):529–37.

Mock J, McPhee SJ, Nguyen T, Wong C, Doan H, Lai KQ, et al. Effective lay health worker outreach and media-based education for promoting cervical cancer screening among Vietnamese American women. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(9):1693–700.

Wang X, Fang C, Tan Y, Liu A, Ma GX. Evidence-based intervention to reduce access barriers to cervical cancer screening among underserved Chinese American women. J Wom Health. 2010;19(3):463–9. 15409996.

Michielutte R, Dignan M, Bahnson J, Wells HB. The Forsyth County Cervical Cancer Prevention Project–II. Compliance with screening follow-up of abnormal cervical smears. Health Educ Res. 1994;9(4):421–32.

Paskett ED, Tatum CM, D'Agostino R Jr, Rushing J, Velez R, Michielutte R, et al. Community-based interventions to improve breast and cervical cancer screening: results of the Forsyth County Cancer Screening (FoCaS) Project. Canc Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8(5):453–9.

Foster JD, Holland B, Louria DB, Stinson L. In situ/invasive cervical cancer ratios: impact of cancer education and screening. J Canc Educ. 1988;3(2):121–5.

Lerman C, Hanjani P, Caputo C, Miller S, Delmoor E, Nolte S, et al. Telephone counseling improves adherence to colposcopy among lower-income minority women. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10(2):330–3.

Miller SM, Siejak KK, Schroeder CM, Lerman C, Hernandez E, Helm CW. Enhancing adherence following abnormal Pap smears among low-income minority women: a preventive telephone counseling strategy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89(10):703–8.

Brewster WR, Hubbell FA, Largent J, Ziogas A, Lin F, Howe S, et al. Feasibility of management of high-grade cervical lesions in a single visit: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2005;294(17):2182–7.

Marcus AC, Kaplan CP, Crane LA, Berek JS, Bernstein G, Gunning JE, et al. Reducing loss-to-follow-up among women with abnormal Pap smears. Results from a randomized trial testing an intensive follow-up protocol and economic incentives. Med Care. 1998;36(3):397–410.

Marcus AC, Crane LA, Kaplan CP, Reading AE, Savage E, Gunning J, et al. Improving adherence to screening follow-up among women with abnormal pap smears: results from a large clinic-based trial of three intervention strategies. Med Care. 1992;30(3):216–30.

Jibaja–Weiss ML, Volk RJ, Smith QW, Holcomb JD, Kingery P. Differential effects of messages for breast and cervical cancer screening. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2005;16(1):42–52.

Rivers SE, Salovey P, Pizarro DA, Pizarro J, Schneider TR. Message framing and Pap test utilization among women attending a community health clinic. J Heal Psychol. 2005;10(1):65–77.

Margolis KL, Lurie N, McGovern PG, Tyrrell M, Slater JS. Increasing breast and cervical cancer screening in low-income women. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(8):515–21.

Jandorf L, Bursac Z, Pulley L, Trevino M, Castillo A, Erwin DO. Breast and cervical cancer screening among Latinas attending culturally specific educational programs. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2008;2(3):195–204.

Fernandez ME, Gonzales A, Tortolero-Luna G, Williams J, Saavedra-Embesi M, Chan W, et al. Effectiveness of Cultivando la Salud: a breast and cervical cancer screening promotion program for low-income Hispanic women. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(5):936–43.

Thompson B, Coronado G, Chen L, Islas I. Celebremos la salud! a community randomized trial of cancer prevention (United States). Canc Causes Contr. 2006;17(5):733–46.

Sox CH, Dietrich AJ, Goldman DC, Provost EM. Improved access to women's health services for Alaska natives through community health aide training. J Community Health. 1999;24(4):313–23.

Suarez L, Roche RA, Pulley LV, Weiss NS, Goldman D, Simpson DM. Why a peer intervention program for Mexican-American women failed to modify the secular trend in cancer screening. Am J Prev Med. 1997;13(6):411–7.

Jibaja–Weiss ML, Volk RJ, Kingery P, Smith QW, Holcomb JD. Tailored messages for breast and cervical cancer screening of low-income and minority women using medical records data. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;50(2):123–32.

Ornstein SM, Garr DR, Jenkins RG, Rust PF, Arnon A. Computer-generated physician and patient reminders. Tools to improve population adherence to selected preventive services. J Fam Pract. 1991;32(1):82–90.

Lantz PM, Soliman S. An evaluation of a Medicaid expansion for cancer care: the Breast and Cervical Cancer Prevention and Treatment Act of 2000. Wom Health Issues. 2009;19(4):221–31.

Peek ME, Cargill A, Huang ES. Diabetes health disparities: a systematic review of health care interventions. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64:101S–156S.

Chin MH, Clarke AR, Nocon RS, Casey AA, Goddu AP, Keesecker NM, Cook SC. A Roadmap and Best Practices for Organizations to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012; doi:10.1007/s11606-012-2082-9.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–926

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Schunemann HJ. GRADE: what is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ 2008;336:995–998.

Carmichael JA, Jeffrey JF, Steele HD, Ohlke ID. The cytologic history of 245 patients developing invasive cervical carcinoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;148(5):685–90.

Janerich DT, Hadjimichael O, Schwartz PE, Lowell DM, Meigs JW, Merino MJ, Flannery JT, Polednak AP. The screening histories of women with invasive cervical cancer, Connecticut. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(6):791–4.

American Cancer Society. Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2011. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2011.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Surveillance of Screening-Detected Cancers (Colon and Rectum, Breast, and Cervix) — United States, 2004–2006]. MMWR 2010; 59(No. SS-9): 2.

Funding Source

Support was provided by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Finding Answers: Disparities Research for Change Program. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation or of Finding Answers: Disparities Research for Change Program.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Glick, S.B., Clarke, A.R., Blanchard, A. et al. Cervical Cancer Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment Interventions for Racial and Ethnic Minorities: A Systematic Review. J GEN INTERN MED 27, 1016–1032 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2052-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2052-2