ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Smoking remains the leading cause of preventable mortality in the US. The national clinical guideline recommends an intervention for tobacco use known as the 5-As (Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, and Arrange). Little is known about the model’s effectiveness outside the research setting.

OBJECTIVE

To assess the effectiveness of tobacco treatments in HMOs.

PARTICIPANTS

Smokers identified from primary care visits in nine nonprofit health plans.

DESIGN/METHODS

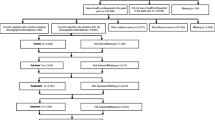

Smokers were surveyed at baseline and at 12-month follow-up to assess smoking status and tobacco treatments offered by clinicians and used by smokers.

RESULTS

Analyses include the 80% of respondents who reported having had a visit in the previous year with their clinician when they were smoking (n = 2,325). Smokers were more often offered Advice (77%) than the more effective Assist treatments–classes/counseling (41%) and pharmacotherapy (33%). One third of smokers reported using pharmacotherapy, but only 16% used classes or counseling. At follow-up, 8.9% were abstinent for >30 days. Smokers who reported being offered pharmacotherapy were more likely to quit than those who did not (adjusted OR = 1.73, CI = 1.22–2.45). Compared with smokers who didn’t use classes/counseling or pharmacotherapy, those who did use these services were more likely to quit (adjusted OR = 1.82, CI = 1.16–2.86 and OR = 2.23, CI = 1.56–3.20, respectively).

CONCLUSIONS

Smokers were more likely to report quitting if they were offered cessation medications or if they used either medications or counseling. Results are similar to findings from clinical trials and highlight the need for clinicians and health plans to provide more than just advice to quit.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2004.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults–United States, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(44):1157–61. November 9.

Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs October 2007 Report. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2007 Oct 10.

Quinn VP, Stevens VJ, Hollis JF, et al. Tobacco-cessation services and patient satisfaction in nine nonprofit HMOs. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(2):77–84. August.

Solberg LI, Boyle RG, Davidson G, Magnan SJ, Carlson CL. Patient satisfaction and discussion of smoking cessation during clinical visits. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(2):138–43. February.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking cessation during previous year among adults–United States, 1990 and 1991. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1993:42:(26)504–7. July 9.

Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline for tobacco cessation. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2000.

Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. US Department of Health and Human Services-Public Health Service; 2008.

Curry SJ, Fiore MC, Orleans CT, Keller P. Addressing tobacco in managed care: documenting the challenges and potential for systems-level change. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;1:S5–S7. 4 Suppl.

Orleans CT. Challenges and opportunities for tobacco control: the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation agenda. Tob Control. 1998;7SupplS8–11.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and managed care: opportunities for managed care organizations, purchasers of health care, and public health agencies. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;RR-14(44):1–12. November 17.

Curry SJ, Orleans CT, Keller P, Fiore M. Promoting smoking cessation in the healthcare environment: 10 years later. Am J Prev Med. 2006 September;31(3):269–72.

National Committee for Quality Assurance 2. The state of health care quality 2007. Washington, DC: 2007.

Hollis JF. Population impact of clinician efforts to reduce tobacco use. In: Population based smoking cessation proceedings of a conference on what works to influence cessation in the general population. National Institutes of Health 2000 November 1;129–54.

Rigotti NA, Quinn VP, Stevens VJ, et al. Tobacco-control policies in 11 leading managed care organizations: progress and challenges. Eff Clin Pract. 2002;5(3):130–6. May.

Stevens VJ, Solberg LI, Quinn VP, et al. Relationship between tobacco control policies and the delivery of smoking cessation services in nonprofit HMOs. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005;35:75–80.

Wagner EH, Greene SM, Hart G, et al. Building a research consortium of large health systems: the Cancer Research Network. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005;35:3–11.

Solberg LI, Hollis JA, Stevens VJ, Rigotti NA, Quinn VP, Aickin M. Does methodology affect the ability to monitor tobacco control activities? Implications for HEDIS and other performance measures. Prev Med. 2003;37(1):33–40. July.

Dillman DA. Mail and telephone surveys: the total design method. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 1978.

Velicer WF, Prochaska JO. A comparison of four self-report smoking cessation outcome measures. Addict Behav. 2004 January;29(1):51–60.

Solberg LI, Quinn VP, Stevens VJ, et al. Tobacco control efforts in managed care: what do the doctors think. Am J Manag Care. 2004 March;10(3):193–8.

Lancaster T, Stead LF. Individual behavioural counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2:CD001292.

Stead LF, Lancaster T. Group behaviour therapy programmes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2:CD001007.

Stead LF, Perera R, Lancaster T. Telephone counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD002850.

Hughes JR, Stead LF, Lancaster T. Antidepressants for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;1:CD000031.

Lancaster T, Stead L, Cahill K. An update on therapeutics for tobacco dependence. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008;9(1):15–22. January.

US Department of Health and Human Services. Reducing Tobacco Use: A Report of the Surgeon General. 2000. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

National Institutes of Health State of the Science Panel. National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science conference statement: tobacco use: prevention, cessation, and control. Ann Intern Med. 2006;14511839–44. December 5.

National Cancer Institute. Greater than the sum: Systems thinking in tobacco control. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Health; 2007.

Fiore MC, Jaen CR. A clinical blueprint to accelerate the elimination of tobacco use. JAMA. 2008 May 7;299(17):2083–5.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults–United States, 1993. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1994;43(50):925–30. December 23.

Patrick DL, Cheadle A, Thompson DC, Diehr P, Koepsell T, Kinne S. The validity of self-reported smoking: a review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(7):1086–93. July.

Quinn VP, Stevens VJ, Smith KS, Ritzwoller D. Documentation of Tobacco Services in the Medical Record: Promoting Treatment and Quality of Care. Oral Presentation, 10th Annual HMO Research Network Conference, Dearborn: MI, May 2004.

Cornuz J, Ghali WA, Di CD, Pecoud A, Paccaud F. Physicians’ attitudes towards prevention: importance of intervention-specific barriers and physicians’ health habits. Fam Pract. 2000;17(6):535–40. December.

Thorndike AN, Rigotti NA, Stafford RS, Singer DE. National patterns in the treatment of smokers by physicians. JAMA. 1998;279(8):604–8. February 25.

Jaen CR, McIlvain H, Pol L, Phillips RL Jr., Flocke S, Crabtree BF. Tailoring tobacco counseling to the competing demands in the clinical encounter. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(10):859–63. October.

Schnoll RA, Rukstalis M, Wileyto EP, Shields AE. Smoking cessation treatment by primary care physicians: An update and call for training. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(3):233–9. September.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted within the Cancer Research Network (CRN), a consortium of non-profit HMOs funded by the National Cancer Institute to increase the effectiveness of preventive, curative, and supportive cancer-related interventions. We are grateful for the work and dedication of the investigators and research staff from the health plans participating in the HMOs Investigating Tobacco (HIT) study: Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound, Seattle, WA; Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, Boston, MA; Health Alliance Plan of Michigan, Detroit, MI; HealthPartners, Minneapolis, MN; Kaiser Permanente Colorado, Denver, CO; Kaiser Permanente Hawaii, Honolulu, HI; Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Oakland, CA; Kaiser Permanente Northwest, Portland, OR; Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Pasadena, CA. Special thanks are given to the staff at the Survey Center at Health Partners. This study was funded by grant U19 CA79689 from the National Cancer Institute.

Conflict of Interest

In the past 3 years Dr. Quinn served as a co-investigator on studies funded by Pfizer and Sanofi-Aventis and Dr. Rigotti served as a consultant to Pfizer and Sanofi-Aventis and received research grants from Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, and Nabi Biopharmaceuticals.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Quinn, V.P., Hollis, J.F., Smith, K.S. et al. Effectiveness of the 5-As Tobacco Cessation Treatments in Nine HMOs. J GEN INTERN MED 24, 149–154 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0865-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0865-9