Abstract

The incidence of HCC is rising worldwide. Studies on ethnicity-based clinical presentation of HCC remain limited. The aim is to compare the clinical presentation and stage of HCC between Asian-Americans and non-Asian-Americans. This retrospective study assessed ethnicity-based differences in HCC presentation, including demographics, laboratory results, diagnosis of underlying liver disease, and stage of HCC. Of 276 patients, 162 were Asian-Americans and 114 were non-Asian-Americans. Compared to non-Asian-Americans, Asian-Americans had a significantly higher incidence of history of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection (55.0% vs. 4.9%, P < 0.001), family history of HBV infection (12.5% vs. 0.0%, P < 0.001) and HCC (15.2% vs. 2.9%, P = 0.002), but lower incidence of history of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection (37.5% vs. 61.6%, P < 0.001). At diagnosis of HCC, Asian-American patients had a significantly lower frequency of hepatic encephalopathy (8.9% vs. 29.3%, P = 0.001), and ascites (26.7% vs. 57.3%, P < 0.001). Asian-Americans had lower Child-Pugh scores (class A: 62.0% vs. 31.4%, P < 0.001), and MELD scores (9.2 ± 4.4 vs. 12.0 ± 6.4, P = 0.02), and presented with a lower stage of HCC by Okuda staging (I: 43.8% vs. 22.8%, P = 0.001). Asian-American patients with HCC presented with a higher incidence of history and family history of HBV infection, lower incidence of hepatic decompensation, lower Child and MELD scores, and an early stage HCC disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common cancer in men and the eighth most common cancer in women worldwide [1], and it constitutes 4.6% of all new cancer cases, 6.3% in men and 2.7% in women [2]. Prognosis of HCC, especially late stage HCC, is usually poor, and it ranks fourth among causes of global cancer mortality [3].

It is well known that the prevalence of HCC is much higher in Asian countries than in other parts of the world [1]. Likewise, in the United States, the highest incidence of HCC was reported in Asian/Pacific Islanders compared to all other ethnic groups [4, 5]. The overall incidence of HCC is rising [6–9], and the risk factors for HCC vary among ethnic groups in the United States. The most commonly noted difference identifies hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection as the most common risk factor in Asians and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and alcoholic cirrhosis as the most common risk factors in non-Asians [10–12]. Survival may also vary between ethnic groups in the United States, although this remains less clear. In a single center study in the Northeast United States, poor prognostic factors were felt to be similar across all races [12]. A study in Hawaii reported significant differences in Child Pugh score and Cancer of the Liver Italian Program Investigators (CLIP) stage between Asians, non-Asians, and Pacific-Islanders with HCC [13]. This study also reported that Asian and Pacific-Islander Americans had lower 1- and 3-year survival rates compared to non-Asians [13]. However, in a registry review of five metropolitan areas in the United States (West Coast, Atlanta, Detroit), increased survival was noted in Asians compared to Whites, Hispanics, and Blacks [14]. In contrast, a study from Southern California reported worse clinical outcomes of HCC in Asian patients than in non-Asian patients [15]. Thus, further studies are needed to address these issues.

In the present study, we retrospectively compared the clinical presentation and stage of HCC between Asian-Americans and non-Asian-Americans in a single university medical center in Southern California.

Patients and Methods

Patient Population

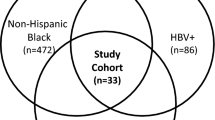

The present study was conducted retrospectively. The study protocol was approved, and informed consent was exempted by the institutional review boards. Medical records of 359 outpatients who presented to the University of California Irvine, Medical Center (UCIMC) between 1999 and 2005 with liver mass lesions presumed to be HCC were consecutively and systematically reviewed. The diagnosis of HCC and inclusion criteria were based on the AASLD guidelines [16] that included: (1) a new diagnosis by pathology; (2) new clinical diagnosis of HCC by alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) >400 ng/ml with one new hepatic defect on imaging, 3 different imaging studies identifying new mass, new defect with massive involvement and death, or new defect with rising AFP; or (3) new probable diagnosis of HCC with new defect seen on 1–2 modes of imaging and treated as HCC [16, 17]. Eighty-three patients were excluded (10 diagnosed in 1998 or earlier, 22 had metastatic cancer but non- HCC, 22 did not have liver mass lesions by repeated imaging, 29 with unlocatable chart). A total of 276 patients were included in the study after exclusion criteria were applied.

Methods and Data Collection

Data that were collected included age, gender, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI); social history (alcohol, tobacco, intravenous drug abuse [IVDA], history of blood transfusion); family history of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HCC; history of viral hepatitis B and C; presence of complications of chronic liver disease at presentation of HCC (including ascites, encephalopathy, coagulopathy by international normalized ratio [INR], and jaundice by total bilirubin). Other laboratory data at presentation of HCC that were collected included serum AFP, platelet count, and imaging findings, including the number and size of the liver lesions and presence of nodes or metastases.

HBV infection was diagnosed by positive hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) or HBV DNA (by PCR) >1,000 copies/ml. HCV infection was diagnosed by positive hepatitis C antibody (anti-HCV), HCV RNA, or documented history of HCV infection. The diagnosis of cirrhosis was based on pathology or clinical criteria, defined as radiographic evidence of a nodular liver, a grossly nodular liver upon direct visualization during surgery, or based on the calculation of the discriminant score [18]. Severity of cirrhosis was determined by calculating the Child Pugh score [19] and Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores [20]. Staging of HCC was assessed by AJCC TNM score [21], Okuda score [22] and CLIP score [23].

Statistical Analyses

The descriptive data were presented as percentage or continuous data with mean with standard deviation. Either Chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, or Student’s t test was used to compare frequencies or means, respectively. Variables with a potential significance (P < 0.10) in univariate analyses were included in multivariate analysis in forward stepwise logistic regression. The odds ratio and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) with associated P values for each variable were reported. A P value of < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Statistical Package for Social Sciences 15.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for data analysis.

Results

Baseline Demographics in Asian-American Versus Non-Asian-American Patients with HCC

As summarized in Table 1, in 276 patients, there were 162 Asian-Americans and 114 non-Asian-Americans. The mean age (61.5 ± 10.6 vs. 60.7 ± 11.6, P = 0.56) and proportion of male patients (80.9% vs. 74.6%, P = 0.21) at diagnosis were similar in both groups. The Asian-American subjects had a significantly lower mean body mass index (24.0 ± 3.6 vs. 27.6 ± 5.5, P < 0.001), incidence of alcohol use (22.5% vs. 49.5%, P < 0.001), tobacco use (47.6% vs. 65.7%, P = 0.004), IVDA (1.4% vs. 19.6%, P < 0.001), and prior transfusion history (35.4% vs. 59.3%, P = 0.009); but a higher incidence of family history of hepatitis B (12.5% vs. 0.0%, P < 0.001) and HCC (15.2% vs. 2.9%, P = 0.002). There was a higher incidence of hepatitis B infection (55.0% vs. 4.9%, P < 0.001) and a lower incidence of hepatitis C (37.5% vs. 61.6%, P < 0.001) in Asian-Americans.

Underlying Cirrhosis in Asian-American Versus Non-Asian-American Patients at Presentation

As summarized in Table 2, the frequency of cirrhosis at HCC presentation was 55.6% in Asian-Americans and 65.8% in Non-Asian-Americans (P = 0.088). Fewer Asian-Americans presented with decompensated liver disease (31.1% vs. 61.3%, P < 0.001), including hepatic encephalopathy (8.9% vs. 29.3%, P = 0.001) and ascites (26.7% vs. 57.3%, P < 0.001). In addition, Child-Pugh scores (class A: 62.0% vs. 31.4%; class B and C: 38.0% vs. 68.6%; P < 0.001) and mean MELD scores (9.2 ± 4.4 vs. 12.0 ± 6.4, P = 0.02) were lower in Asian-Americans than in non-Asian-Americans.

HCC Stage in Asian-American Versus Non-Asian-American Patients at Presentation

Asian-Americans presented with an earlier stage of HCC by Okuda (I: 43.8% vs. 22.8%; II and III: 56.3% vs. 77.2%; P = 0.001), but not by AJCC TNM or CLIP score system (data not shown). A subsequent analysis of variables that may be associated with Okuda HCC staging was then performed. As summarized in Table 3, the male patients were more likely to present with early stage HCC (Okuda I) than late stage HCC (Okuda II and III) on univariate analysis (87.0% vs. 74.8%, P = 0.034). Risk factors associated more with later Okuda stages II and III than early Okuda stage I on univariate analysis include alcohol use (40.1% vs. 26.7%, P = 0.05) and IVDA (12.4% vs. 2.9%, P = 0.036). Subjects with a family history of HCC tended to present with earlier Okuda stage. Additionally, elevated serum AFP, AST, AST/ALT ratio, and presence of hepatic encephalopathy were associated with Okuda stage II-III HCC. As summarized in Table 4, multivariate analysis indicated that race was an independent predictor of Okuda stage of HCC. That is, Asian-American patients are more likely to present with Okuda stage I, while non-Asian-Americans are more likely to present with Okuda stage II-III. Additionally, an AST/ALT ratio ≥1, AST ≥ 40 IU/l, and serum AFP ≥400 ng/ml were also independently associated with Okuda staging II-III HCC.

HCC Presentation in Patients with HBV Infection Versus HCV Infection

As summarized in Table 5, the majority of HCC patients with chronic HBV were Asian-Americans (95.2%) while less than half the HCC patients with chronic HCV were Asian-American (45.2%, P < 0.001). There were more male HCC patients with HBV than HCV (88.9% vs. 73.0%, P = 0.034). A history of IVDA (0% vs. 19.5%, P < 0.001) and blood transfusion before 1992 (17.4% vs. 65.7%, P < 0.001) were less likely in HCC patients with chronic HBV infection compared to those with chronic HCV. A family history of hepatitis B (28.3% vs. 0%, P = 0.098) was more likely to occur in HCC patients with chronic HBV infection compared to those with chronic HCV. The frequencies of cirrhosis, hepatic decompensation (by ascites and hepatic encephalopathy), and higher Child class (i.e., B and C) were significantly higher in patients with HCC and chronic HCV infection than in those with HCC and chronic HBV infection. Consistently, the frequencies of thrombocytopenia, a high AST/ALT ratio, and hypoalbuminemia were significantly higher in those with HCC and chronic HCV infection. HCC patients with HBV had lower Child Pugh scores compared to those with HCV. However, HBV or HCV infection was not associated with MELD score or Okuda stage of HCC in these patients.

When further comparing the clinical presentation of HBV-related versus HCV-related HCC in 117 Asian-American patients, elevated ALT and AST were significantly higher in HBV-related versus HCV-related HCC [ALT: 42/47 (89.4%) vs. 35/52 (67.3%); AST: 44/48 (91.7%) vs. 38/51 (74.5%)]. Presentation of cirrhosis and Child-Pugh class B and C were less common, but not significantly different, in HBV-related than in HCV-related HCC [Cirrhosis: 32/60 (53.3%) vs. 40/57 (70.2%); Child B/C: 8/27 (29.6%) vs. 16/36 (44.4%)]. Other parameters, including age, gender, history of alcohol use, IVDU or transfusion, and family history of HCC were not significantly different in both groups.

Discussion

The most significant conclusion from this study is that Asian-Americans with HCC in our cohort presented with earlier stage liver disease compared to non-Asian-Americans. Though not statistically significant, fewer Asian-Americans had cirrhosis. However, the Asian-Americans who did have cirrhosis had statistically significant earlier stage cirrhosis by Child-Pugh and MELD score. Furthermore, being Asian-American was independently associated with lower Okuda score on multivariate analysis. There may be several explanations for these findings.

One main reason is the higher incidence of HBV in the Asian-American patients with HCC compared to non-Asian HCC patients, which has been shown in this study as it has in many previous studies. There is a higher incidence of HCC in pre-cirrhotic individuals with HBV, and chronic HBV infection can promote hepatocarcinogenesis in the absence of cirrhosis [24]. When HBV patients with HCC and HCV patients with HCC were directly compared in our study, those with HBV did have significantly lower Child Pugh scores than those with HCV. However, the mean MELD score and Okuda score were not significantly different in both groups.

Two other possible explanations for earlier stage liver disease in Asian-Americans with HCC are the lower incidence of alcohol use in Asian-Americans and the lower percentage of Asian-American patients with BMI ≥ 30. Previous studies have linked excessive alcohol use to the development of HCC [25, 26], and concomitant alcohol use in the setting of other underlying liver disease may accelerate the progression of liver disease. The same line of reasoning may be used for patients with a BMI ≥30 as these patients are at increased risk of developing non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and fibrosis [27].

One other possible explanation for the earlier stage liver disease in our cohort of Asian-Americans with HCC is implementation of HCC screening. It has been reported that healthcare providers with Asian language abilities and greater knowledge of HBV risk factors and screening guidelines were more likely to screen for HBV [28, 29]. Given the high number of Southeast Asians who live in Southern California, it cannot be discounted that healthcare providers taking care of our cohort of patients may been more aware of specific issues related to Asian-Americans, such as higher incidence of HBV and the need to screen for HCC. However, further studies will be needed to determine whether appropriately screened patients actually resulted in an earlier diagnosis of HCC in these patients.

Our study emphasizes another important point that is often overlooked. Although HBV is very prevalent in the Asian community as a cause of HCC, HCV is also important and accounted for 37% the HCC in Asian patients in this study. This is consistent with the reported prevalence of HCV in Asian populations at 3–8% in Southeast Asia [30]. Though HCV-cirrhosis is more often associated with HCC [31–34], a significant incidence of HCC was found in patients with pre-cirrhotic fibrosis in the prospective HALT C trial [35, 36]. It is clear that besides HBV, HCV is also a major cause of HCC in the Asian population. These patients should be identified and screened regularly along with those patients with hepatitis B.

The presence of cirrhosis and hepatic decompensation may impact the management and outcome of HCC. Decompensated liver disease may contraindicate surgical resection [37–39], or other ablation therapies, such as radiofrequency ablation [39–41]. Wong et al. reported that Asian and Pacific-Islander American patients with HCC presented with earlier stage cirrhosis compared to non-Asian American patients [13]. However, as treatment data and survival data were not collected, this present study was not able determine whether a lower frequency of decompensated cirrhosis, together with earlier stage of HCC, would imply a better outcome of HCC in Asian-American patients, which has been reported previously [14, 42, 43].

In summary, in our single center cohort study of HCC patients, being Asian-American was an independent risk factor predicting earlier Okuda stage on multivariate analysis, and Asian-Americans presented with earlier stage cirrhosis. Obviously, there were severe limitations to our study, including the retrospective nature of the study, referral bias, and the study being solely at a single tertiary care center. Additionally, the present study was not able to compare HCC presentation among subgroups of Asian Americans. Thus, the results should be interpreted with caution. Nevertheless, our study underscores the need for further prospective studies to identify specific factors placing patients at higher risk for HCC and to appropriately screen these patients in hopes of an earlier diagnosis and, therefore, better options for managing HCC.

References

Bosch FX, Ribes J, Cleries R, et al. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Liver Dis. 2005;9:191–211. v. Review.

Kew MC. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Toxicology. 2002;181–182:35–8.

Bosch FX, Ribes J, Borras J. Epidemiology of primary liver cancer. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19:271–85.

Howe HL, Wu X, Ries LA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2003, featuring cancer among U.S. Hispanic/Latino populations. Cancer. 2006;107:1711–42.

Wong R, Corley DA. Racial and ethnic variations in hepatocellular carcinoma incidence within the United States. Am J Med. 2008;121:525–31.

El-Serag HB, Mason AC. Rising incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:745–50.

El-Serag HB, Davila JA, Petersen NJ, McGlynn KA. The continuing increase in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States: an update. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:817.

Davila JA, Morgan RO, Shaib Y, et al. Hepatitis C infection and the increasing incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1372–80.

Davila JA, Petersena NJ, Nelson HA, et al. Geographic variation within the United States in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:487–93.

Hwang SJ, Tong MJ, Lai PP, et al. Evaluation of hepatitis B and C viral markers: clinical significance in Asian and Caucasian patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States of America. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;11:949–54.

Di Bisceglie AM, Lyra AC, Schwartz M, et al. Hepatitis C-related hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States: influence of ethnic status. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2060–3.

Stuart KE, Anand AJ, Jenkins RL. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Prognostic features, treatment outcome, and survival. Cancer. 1996;77:2217–22.

Wong LL, Limm WM, Tsai N, Severino R. Hepatitis B and alcohol affect survival of hepatocellular carcinoma patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3491–7.

Davila JA, El-Serag HB. Racial differences in survival of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States: a population-based study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:104–10. quiz 4-5.

Chin PL, Chu DZ, Clarke KG, Odom-Maryon T, Yen Y, Wagman LD. Ethnic differences in the behavior of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;85:1931–6.

Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2005;42:1208–36.

Park JW, An M, Choi JI, et al. Accuracy of clinical criteria for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma without biopsy in a hepatitis B virus-endemic area. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2007;133:937–43.

Bonacini M, Hadi G, Govindarajan S, Lindsay KL. Utility of a discriminant score for diagnosing advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1302–4.

Child CG, Turcotte JG. Surgery and portal hypertension. In: Child CG, editor. The liver and portal hypertension. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1964. p. 50–64.

Malinchoc M, Kamath PS, Gordon FD, et al. A model to predict survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Hepatology. 2000;31:864–71.

Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, et al. AJCC cancer staging manual, 6th ed. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. p. 131.

Okuda K, Ohtsuki T, Obata H, et al. Natural history of hepatocellular carcinoma and prognosis in relation to treatment. Study of 850 patients. Cancer. 1985;56:918–28.

The Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP) Investigators. Prospective validation of the CLIP score: a new prognostic system for patients with cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2000;31:840.

Yu MW, Chen CJ. Hepatitis B and C viruses in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1994;17:71–91.

Donato F, Tagger A, Gelatti U, et al. Alcohol and hepatocellular carcinoma: the effect of lifetime intake and hepatitis virus infections in men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:323–31.

Donato F, Tagger A, Gelatti U, et al. Alcohol and hepatocellular carcinoma: the effect of lifetime intake and hepatitis virus infections in men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:323–31.

Hu XS, Kyulo NL, Xia VW, et al. Factors associated with hepatic fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C: a retrospective study of a large cohort of US patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:758–64.

Lai CJ, Nguyen TT, Hwang J, et al. Provider knowledge and practice regarding hepatitis B screening in Chinese-speaking patients. J Cancer Educ. 2007;22:37–41.

Hu KQ. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in Asian and Pacific Islander Americans (APIAs): how can we do better for this special population? Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1–10.

Hepatitis C. Global prevalence. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 1997;72:341.

Tradati F, Colombo M, Mannucci PM, et al. A prospective multicenter study of hepatocellular carcinoma in Italian hemophiliacs with chronic hepatitis C. The study group of the association of Italian hemophilia centers. Blood. 1998;91:1173–7.

Fattovich G, Giustina G, Degos F, et al. Morbidity and mortality in compensated cirrhosis type C: a retrospective follow-up study of 384 patients. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:463–72.

Brechot C. Hepatitis C virus 1b, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 1997;25:772–4.

But DY, Lai CL, Yuen MF. Natural history of hepatitis-related hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1652–6.

Welzel TM, Morgan TR, Bonkovsky HL. Variants in interferon-alpha pathway genes and response to pegylated interferon-alpha2a plus ribavirin for treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the hepatitis C antiviral long-term treatment against cirrhosis trial. Hepatology. 2009;49:1847–58.

Lok AS, Seeff LB, Morgan TR, et al. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma and associated risk factors in hepatitis C-related advanced liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(1):138–48 (Epub 2008 Sep 18).

Llovet JM, Schwartz M, Mazzaferro V. Resection and liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2005;25:181–200.

Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2003;362:1907–17.

Masuzaki R, Omata M. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2008;27:113–22.

Shiina S, Teratani T, Obi S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of radiofrequency ablation with ethanol injection for small hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:122–30.

Tateishi R, Shiina S, Teratani T, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. An analysis of 1000 cases. Cancer. 2005;103:1201–9.

Hwang JP, Hassan MM. Survival and hepatitis status among Asian Americans with hepatocellular carcinoma treated without liver transplantation. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:46.

Tong MJ, Chavalitdhamrong D, Lu DS, et al. Survival in Asian Americans after treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma: a seven-year experience at UCLA. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009; 9 (Epub ahead of print).

Disclosures

There are no financial disclosures related to this study from any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Wong, P.Y., Xia, V., Imagawa, D.K. et al. Clinical Presentation of Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) in Asian-Americans Versus Non-Asian-Americans. J Immigrant Minority Health 13, 842–848 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-010-9395-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-010-9395-8